Clostridium perfringens is an anaerobic gram-positive spore-forming bacillus and is associated with acute gastrointestinal infections. C. perfringens possesses a diverse collection of toxins responsible for disease pathogenesis and can form spores resistant to environmental stress. This gram-positive bacterium is associated with acute gastrointestinal infections ranging in severity from diarrhea to necrotizing enterocolitis and myonecrosis in humans. It is ubiquitous and is easily found in soil, decaying vegetation and as a part of normal intestinal microbiota of humans and animals.

Classification

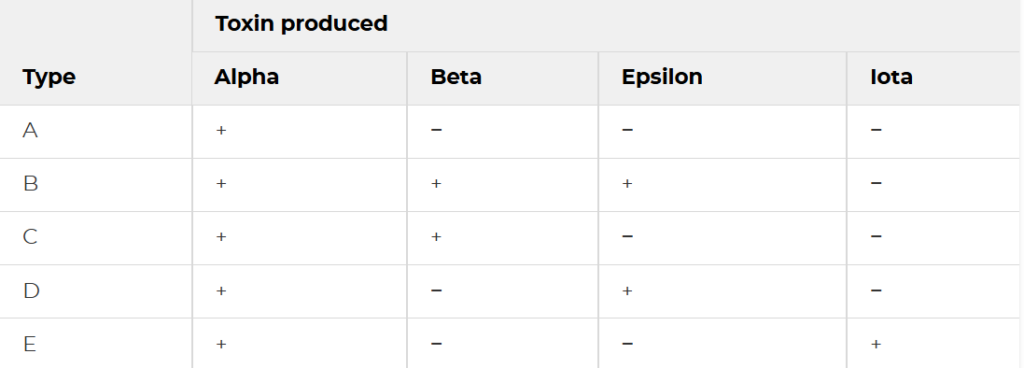

The classification of C. perfringens is based on the production of six major toxins: alpha-toxin (CPA), beta-toxin (CPB), epsilon toxin (ETX), iota-toxin (ITX), enterotoxin (CPE) and necrotic enteritis B-like toxin (NetB).

- A: CPA only

- B: CPA, CPB ETX

- C: CPA, CPB, CPE (+/-)

- D: CPA, ETX, CPE (+/-)

- E: CPA, ITX, CPE (+/-)

- F: CPA, CPE

- G: CPA, NetB

Morphology and Microscopy

Microscopy

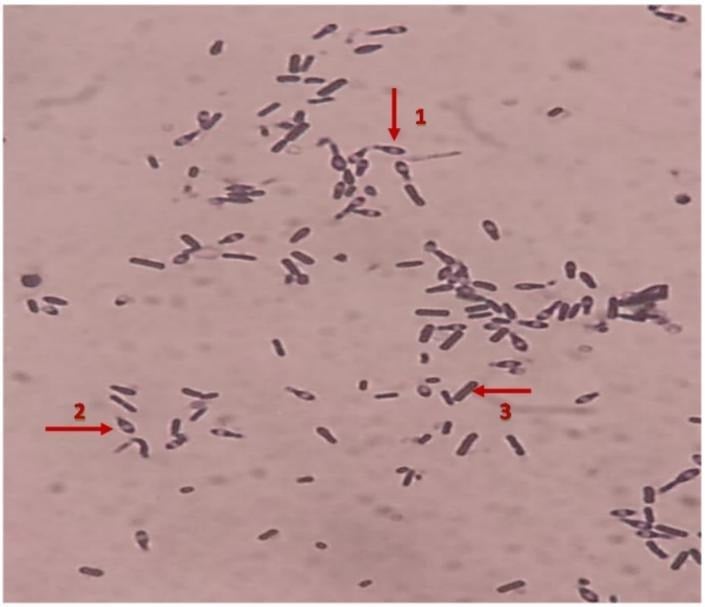

As a member of Bacillota, it exhibits classic features that can be observed using both light and electron microscopy, revealing details from its overall cellular shape to the ultrastructure of its resilient spores.

C. perfringens is a rod-shaped bacterium. When observed under microscope after performing Gram staining, it consistently retains the crystal violet dye, making it gram-positive. This indicates the presence of a thick peptidoglycan layer in its cell wall. Under the light microscope, the presence of a capsule surrounding the cell can also be observed. This capsule is a feature that contributes to its virulence by protecting it from phagocytosis.

Morphology

The colonies formed by C. perfringens on solid media like yeast extract blood agar, are not uniform. The ununiform colonies range from glossy colonies with isolated margins to flat colonies with filamentous margins. This variation in colony morphology can be an important clue in laboratory identification. These colonies typically measure to be 3–8 µm in length and 0.4 – 1.2 µm in diameter. The cells are described as pleomorphic, which means they can exhibit variation in shape, appearing as straight or slightly curved rods.

In blood agar, they show a double zone of hemolysis i.e., complete hemolysis is shown in the inner zone while there is partial hemolysis of blood agar on the outer zone. On Marshal’s medium, C. perfringens gives black colonies, in MacConkey Agar, it gives green fluorescent colonies.

Endospore formation is the defining characteristic of the genus Clostridium. The spores produced are sub-terminal in location and non-bulging but wider than the cells. This width of the spore sometimes gives the cell a swollen, spindle-like appearance. In infected host tissue, these tissues can be readily observed.

Cultural and Growth Characteristics

C. perfringens is a gram-positive, rod shaped, spore forming, nonmotile anaerobe belonging to phylum Bacillota. Although classified as an obligate anaerobe, it demonstrates a degree of aerotolerance, allowing brief survival in oxygenated environments.

C. perfringens is a fastidious organism with complex nutritional demands. It requires 13 essential amino acids for growth (including valine, isoleucine, leucine, methionine, tryptophan, arginine, cysteine). It is an anaerobic bacterium but can grow under micro-aerophilic conditions. It can grow over a pH range of 5.5 – 8 and temperature range of 20oC -50oC (optimal being 45oC). Its generation time is as short as 7-10 minutes under optimal conditions. This unusually short doubling time is one of the reasons why the organism is frequently implicated in foodborne outbreaks when cooked food is improperly cooled or held at warm temperatures. The functional range of C. perfringens is mildly acidic to mildly alkaline conditions in terms of pH with its optimal growth near neutral pH. This adaptability enables growth in diverse environments.

The organism requires a relatively high-water activity, with a growth range of 0.93 to 0.97. This explains its prevalence in moist foods rather than in dried or preserved products.

Sporulation

Sporulation in C. perfringens is a survival response triggered by nutrient deprivation. These spores are heat resistant and can survive cooking temperatures that destroy most of the competing bacteria. During the slow cooling or improper storage, spores germinate into vegetative cells, leading to rapid bacteria multiplication.

Epidemiology

Clostridium perfringens represents one of the most widespread bacterial pathogens with ubiquitous environmental distribution in soil, sewage, food and normal intestinal flora of humans and animals. This organism ranks as the second most common bacterial cause of foodborne illness.

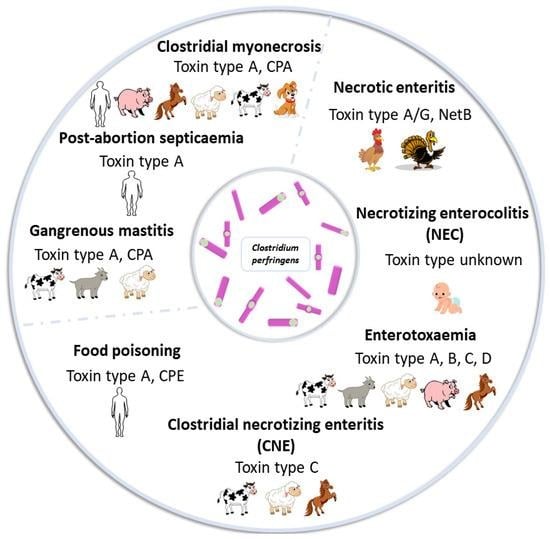

The remarkable pathogenic versatility of C. perfringens stems from its extensive arsenal of virulence factors, with over 20 different toxins and enzymes identified to date. These toxins are functionally classified into 4 categories: membrane damaging enzymes, pore forming toxins, intracellular toxins and hydrolytic enzymes. The production patterns of four typing toxins- alpha, beta, epsilon and iota, forms the basis for classifying isolates into 7 toxinotypes (A through G).

Type A and Type C toxins are known to cause human disease. Type A is responsible for most C. perfringens associated with food poisoning and non-foodborne diarrheal disease. Type C has been associated with endemic enteritis necroticans.

Clostridial toxins are biologically active proteins that are antigenic in nature and can therefore be neutralized with specific antisera. Detection of particular toxins in a patient sample may be diagnostic and therefore render isolation of organism unnecessary.

Figure 2 perfringens toxin types

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Classification-of-C-perfringens_tbl1_304924310

Pathogenesis and Virulence

The different toxinotypes of C. perfringens produce a wide variety of diseases in both animals and humans, which ranges from C. perfringens Type A gas gangrene to several enterotoxemia and enteritis syndromes. All of these diseases are mediated by one or more toxins of C. perfringens. The pathogenesis is mainly due to a complex repertoire of exotoxins and degradative enzymes that the bacterium produces during growth and sporulation. Most C. perfringens toxins function as pore forming proteins that insert into host cell membranes, creating channels that disrupt ionic balance and osmotic stability, ultimately leading to cell swelling and hence, death. Other toxins possess enzymatic activities, such as phospholipases that degrade membrane lipids/

Pathogenesis of C. perfringens follows distinct pathways depending on the route of exposure and specific toxins produced. In most common human diseases caused by this organism (in foodborne illness), pathogenesis begins by ingestion of food containing a large number of vegetative cells. These cells pass through the acidic environment of the stomach and reach the small intestine, where they sporulate in response to the alkaline environment. During this sporulation, enterotoxin is produced and accumulated within the bacterial cell until the spore is released, at which point the enterotoxin is liberated into the intestinal lumen. The released enterotoxin then binds to specific receptor proteins on the surface of the intestinal epithelial cells, forming a complex that inserts into the cell membrane to create a pore which allows calcium ions to enter into the cell. This activates the enzymes that trigger cell death through both apoptosis and oncosis. This results in fluid accumulation and tissue damage characteristic of diarrheal disease.

Non-toxin Virulence Factors and Regulation

Non-toxin factors like sialidases, collagenases, etc., are being implicated in pathogenicity of C. perfringens. Sialidases degrade the intestinal mucus, exposing the bacterial adherence and generating nutrients for bacterial growth. Collagenases and hyaluronidase degrade the extracellular matrix components facilitating tissue invasion and spread. The enzymes and toxins produced by C. perfringens play essential roles in intestinal colonization, immunological evasion, intestinal micro-ecosystem imbalance and intestinal mucosal disruption, all influencing host health.

The type IV pili of C. perfringens that aids the organism in motility also contribute to other potentially virulence-related functions like biofilm production and adherence.

Enterotoxins

Enterotoxin (CPE) responsible for human food poisoning and antibiotic-associated diarrhea, is produced during sporulation and binds to claudin receptors on intestinal epithelial cells, forming a pore complex that allows calcium influx and triggers cell death through either apoptosis or necroptosis depending on the toxin dose. The resulting tissue damage causes fluid and electrolyte losses from the intestines, producing characteristic diarrheal symptoms of CPE-mediated diseases.

NetB toxin produced by type G strains forms pores in intestinal epithelial cells causing massive necrosis of the intestinal lining. C. perfringens produces other accessory toxins apart from the major toxins such as perfringolysin O (PFO), neta2 toxin, BEC, etc.

Clinical Manifestations

Disease caused: Food poisoning (self-limiting, most common), Gas gangrene (severe cases)

The most common presentation is C. perfringens food poisoning which typically begins 6 to 24 hours after ingestion of contaminated food. The person infected experiences watery diarrhea and abdominal cramps as the predominant symptoms with vomiting and fever occurring only rarely. It is usually mild and self-limiting, resolving within around 24 hours without any medical intervention. Severe cases may progress to dehydration, abdominal distention from gas accumulation and even hypovolemic shock.

A far more severe manifestation is clostridial myonecrosis, also known as gas gangrene. The clinical presentation is characterized by sudden onset of severe pain that often appears disproportionate to physical findings. Bacteremia occurs in about 15% of the cases and may be accompanied by massive intravascular hemolysis, acute kidney injury and multiorgan failure.

One reason for complication during treatments is the ability of these organisms to produce biofilms. These biofilms produced confer augmented resistance against environmental challenges and antimicrobial interventions, contributing to disease persistence and recurrence.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Specimens: stool samples (food poisoning), wound exudate/tissue biopsies (gas gangrene), blood cultures (septicemia), food samples (in case of outbreaks)

Culture

For culture, specimens are inoculated into blood agar enriched with yeast extract, vitamin K and haemin and then incubated under anaerobic conditions with hydrogen supplement and carbon dioxide (5-10%) for 48 hours. The organism growth exhibits characteristic colonial morphology showing circular, grey colonies surrounded by a distinctive zone of double hemolysis on blood agar.

For selective isolation, media like Perfringens Selective Agar (PSA) and neomycin-polymyxin supplemented blood agar are recommended to suppress competing flora.

Even though the traditional culture methods remain as the backbone of diagnosis, it is time-consuming and has limited sensitivity and also cannot differentiate between toxin types.

Biochemical and Identification Tests

The C. perfringens appears as large, gram-positive rods that may be slightly curved. It is non-motile. As for the catalase and oxidase test, the organism shows negative reactions to both the tests and are fermentative in nature with the ability to ferment glucose, sucrose and lactose while hydrolyzing esculin.

A key diagnostic test is the Nagler reaction. This test detects the alpha toxin produced by the organism. The production of the said toxin is demonstrated by the precipitation lines on egg yolk agar with specific antitoxin neutralization. Even with the advancement in biochemical identification systems, biochemical identification alone cannot determine the toxin type of an isolate.

Toxin Detection by Immunological Methods

Serological detection of C. perfringens is important for the confirmation of diagnosis and determination of the toxinotypes.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is a widely used toxin detection system in clinical specimens like feces, bodily fluids. The ELISA kits enable the simultaneous detection of α, β and ε toxins from intestinal contents of livestock.

Fluorescent antibody test is another immunological method applicable for detecting histotoxic clostridia in tissue specimens.

Molecular methods

Molecular techniques have revolutionized the diagnosis and typing of C. perfringens by offering rapid, sensitive and specific detection directly from the clinical specimens.

Conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) enables specific detection of the organism with the detection limit as low as 5*102 bacteria in stool samples.

Multiplex PCR is useful for toxin typing, simultaneously detecting genes encoding α, β, ε, ι and enterotoxins to classify isolates into toxinotypes A through G.

Real-time quantitative PCR offers enhanced sensitivity and quantification and detecting toxin genes directly from the intestinal contents and enabling differentiation types A, B, C and D with high accuracy.

Combining conventional culture methods with PCR techniques provides the most reliable detection approach for Clostridium species while also determining their toxigenic potential.

Treatment

Most of the C. perfringens associated with acute diarrheal diseases are self-limiting and so, only supportive care is needed to maintain euvolemic state. For these cases, antibiotics are generally not indicated. Those who are hospitalized need fluid resuscitation and an advancing diet when tolerated.

However, a medical emergency is the clostridial sepsis. This case often presents in septic shock with possible intravascular hemolysis due to CPA-mediated destruction of red blood cells. Early antibiotic treatment with penicillin G and clindamycin, tetracycline or metronidazole in combination with survival debridement of necrotic tissue may help to prevent death. Even with appropriate treatment, mortality rate of myonecrosis is 20-30% while mortality rate without treatment is 100%.

Generally, there are no complications regarding the food poisoning and non-foodborne diarrheal diseases if adequately managed. However, blood-stream infection can result in toxin-mediated intravascular hemolysis and septic shock.

Prevention and Control

Most of the food poisoning and non-foodborne diarrheal diseases from C. perfringens are due to undercooked meat or poultry. Awareness regarding food safety protocols is essential for preventing and limiting the spread of disease.

Leftover food should be refrigerated to temperature below 4°C within 2 hours of preparation. The bacteria multiply rapidly in foods left in the temperature between 4° to 60°C. The leftovers should be reheated to at least 74°C before serving. When reheating leftovers, the internal temperature must reach about 75°C or more with core temperature maintained for at least 30 seconds to ensure vegetative cells are destroyed.

Conclusion

Clostridium perfringens is a formidable bacterial pathogen of significant public health importance causing a large number of food poisoning cases annually. It is ubiquitous and has an ability to form spores. This organism has a rapid doubling time of less than 10 minutes which makes it a persistent challenge for food safety and clinical management. The extensive arsenal of C. perfringens toxins and enzymes enables it to cause a diverse spectrum of diseases from self limiting gastroenteritis to life threatening gas gangrene.

Pathogenesis is driven by complex molecular mechanisms which involve pore forming toxins and enzymes that can disrupt host cell membranes, degrade extracellular matrices and subvert immune responses. Non-toxin virulence factors further enhance colonization and pathogenicity.

Effective control requires multifaceted approaches tailored to specific disease contexts. For food borne illnesses, temperature management should be strict. In processed foods, various chemical interventions to inhibit growth of organisms in the food should be used.

References

Ahmad, N. H., et al. (2024). Growth and no-growth boundary of Clostridium perfringens in cooked cured meats – A logistic analysis and development of critical control surfaces using a solid growth medium. Food Research International, *191*, 114701.

Aryal, S. (2023). Clostridium perfringens: An overview. Microbe Notes. Retrieved February 15, 2026, from https://microbenotes.com/clostridium-perfringens/

Camargo, A., Ramírez, J. D., Kiu, R., Hall, L. J., & Muñoz, M. (2021). Pathogenicity and virulence of Clostridium perfringens. Virulence, *12*(1), 723-753. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2021.1886777

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024a). About C. perfringens food poisoning. Retrieved February 15, 2026, from https://www.cdc.gov/clostridium-perfringens/about/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024b). Preventing C. perfringens food poisoning. Retrieved February 15, 2026, from https://www.cdc.gov/clostridium-perfringens/prevention/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024c). Testing for C. perfringens infection. Retrieved February 15, 2026, from https://www.cdc.gov/clostridium-perfringens/testing/index.html

Centre for Food Safety. (2024, January 24). Suspected food poisoning alert. Hong Kong Government. Retrieved February 15, 2026, from https://www.cfs.gov.hk/english/whatsnew/whatsnew_sfpa/whatsnew_sfpa_20240124_01.html

Hernández, M., & Rodríguez-Lázaro, D. (2015). Detection of Clostridium perfringens. In Molecular Microbial Diagnostic Methods: Pathways to Implementation for the Food and Water Industries. ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378113515000681

Juneja, V. K., et al. (2006). Control of Clostridium perfringens in cooked ground beef by carvacrol, cinnamaldehyde, thymol, or oregano oil during chilling. Journal of Food Protection, *69*(7), 1546-1551.

Li, J., Zhou, Y., Yang, D., Zhang, S., Sun, Z., Wang, Y., … & Wang, J. (2024). Clostridium perfringens in the intestine: Innocent bystander or serious threat? Microorganisms, *12*(8), 1610. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12081610

Microbes Info. (2015). Clostridium perfringens: Morphology, cultural characteristics, classification and laboratory diagnosis. Retrieved February 15, 2026, from http://microbesinfo.com/2015/02/clostridium-perfringens-morphology-cultural-characteristics-classification-and-laboratory-diagnosis/

National Center for Biotechnology Information. (2024). Clostridium perfringens infection. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved February 15, 2026, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559049/

North Dakota Department of Health and Human Services. (2024). Clostridium perfringens factsheet. Retrieved February 15, 2026, from https://www.hhs.nd.gov/clostridium-perfringens-factsheet

Obana, N., Nakamura, K., & Nomura, N. (2014). A sporulation factor is involved in the morphological change of Clostridium perfringens biofilms in response to temperature. Journal of Bacteriology, *196*(8), 1540-1550. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.01444-13

SIMPIOS. (2024). Clostridium perfringens: Factsheet. Retrieved February 15, 2026, from https://www.simpios.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/id8_3_2_rev_en_Cdifficile140310.pdf

Talukdar, P. K., et al. (2016). Inactivation strategies for Clostridium perfringens spores and vegetative cells. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, *83*(1), e02731-16.

University of Texas at Arlington. (n.d.). Clostridium perfringens: Biological safety data sheet. Environmental Health and Safety. Retrieved February 15, 2026, from https://www.uta.edu/campus-ops/ehs/biological/docs/PSDS/CLOSTRIDIUM%20PERFRINGENS.pdf