What is Elasticity?

Elasticity is the strength providing property for a material. Here ‘’strength’’ means the behavior of opposing the deforming force acting on it. Elasticity is that quality which gives reformation of the original state of a material after removing that force. Actually, the hardness or stiffness of the material provides this strength to overcome the force. A tightly packed material gains the restoring force from its internal bonding of the molecules and hence the object is said to be elastic.

There are various common examples of elasticity around us. The most familiar one is the stretched rubber. If the stretching force (deforming force) is removed it flaps back to the original condition. If the rubber cannot attain its initial state and gets loosen or breaks, the property is called plasticity.

Force affects a body by changing its shape, size, volume or a dimension of the body. These are the physical changes suffered by a body which is called deformation. Hence, the reaction of the objects to any external force is to be studied to understand the nature of that object. The nature of every material around us is different. A steel or iron rod is very hard while a sponge is very soft. Hence, when a force is applied they deform to some limits. The softer objects cannot regain their originality while the harder ones do not show changes after removing the force. Also, no material is ideally rigid and the deformation of some materials cannot be visible. These deformations are calculated with micro analysis. Hence, understanding elasticity allows us to design large constructions to simple applications to make our life easier and safer.

Perfectly Elastic vs. Perfectly Plastic Bodies: Understanding the Difference

Elastic bodies can be understood well by comparing them with plastic bodies. Materials are either elastic or plastic. A perfectly elastic body is the ideal body which completely comes to the original shape and size after the external force is removed. But this elasticity falls for a very large external force (deforming force). They do not have permanent deformations. The potential energy stored in the body gives it the required restoring force to recover it from deformation. However, no realistic bodies are ideally elastic as friction, air resistance or certain factors may have an invisible effect on them. We can have approximately elastic bodies like steel, quartz etc. under the elastic limit.

Perfectly plastic bodies are those which show permanent deformation on applying force. They may have a new shape, size or dimension after release. Materials like wet clay, putty, or dough etc. have plastic nature. They are also approximately as no perfect extreme conditions can be achieved. For greater forces steel and quartz also behave as plastic.

Thus, plastic and elastic nature must be identified before any applications. The amount of external force that makes the body plastic should also be studied carefully and precisely. This difference is very important in structural design and engineering. Large structures like buildings, bridges can deform the surface permanently if proper restoring force is not developed. This may cause serious damage.

Stress and Strain: The Forces Behind Deformation

While applying deforming force, two quantities can be measured: amount of deforming force and the changes in shape, size or dimension done by the deforming force which are simply known as stress and strain respectively.

Mathematically, stress is defined as the force applied per unit area of the material i.e.

Stress = Force / Area [Equation 1]

Stress is mathematically equal to pressure, and both have same unit i.e. N/m2 or Pascal (Pa).

From equation (1) we can see that stress is directly proportional to force and inversely proportional to the area. Hence, greater the force, the material experiences greater stress. Similarly, for larger surface area stress would be smaller for the material.

The different types of stress are:

- Tensile stress: Stress applied on objects by stretching. For example, stretching a rubber tube.

- Compressive stress: Stress applied on objects by compressing or squeezing. For example, making a dough.

- Shear stress: When force is parallel to the layers of a surface and making one layer slide over another. For example, soaking a towel or tearing a paper.

Mathematically, strain is defined as the change in dimension per unit original dimension of the object, where the change in dimension is caused by the deforming force. Unlike stress it has no unit as it is the ratio of two same quantities and is given as,

Strain = ΔL / L (For stretched length)

Different types of strain are,

- Longitudinal strain: Ratio of change in length and original length.

- Lateral strain: Ratio of change in diameter and original diameter.

- Shear strain: Ratio of change in angle between two originally perpendicular lines.

Stress and strain are the cause and effect and hence no strain occurs without stress.

Hooke’s Law: The Linear Relationship Between Force and Extension

All the elastic and plastic properties of the materials are based on Hooke’s Law. This law was discovered by the scientist Robert Hooke in the 17th century.

It states that the extension or displacement produced on a material by an external force is directly proportional to the force applied but the force should be within the elastic limit. The elastic limit is the boundary condition where the object loses its elasticity and becomes plastic. Simply, Hooke’s law says that the extension or displacement of a material will be larger if the applied force is large enough but within a certain condition. The force and displacement have a linear relationship and mathematically given as,

F ∝ x

or

F = -kx [Equation 2]

Here:

- F is the applied force,

- x is the extension (change in length),

- k is the proportionality constant known as the spring constant. The value of k differs as per the nature of the material.

An object having larger spring constant means the object is very stiff having greater restoring force and vice-versa. A negative sign denotes that the restoring force is applied opposite to the deforming force.

Hooke’s Law is very useful in many practical applications. It is used in:

- Springs in vehicles to absorb shocks,

- Weighing machines,

- Mechanical balances,

- Vibration systems and many engineering devices.

The Stress-Strain Curve: Elastic Limit, Yield Point, and Fracture

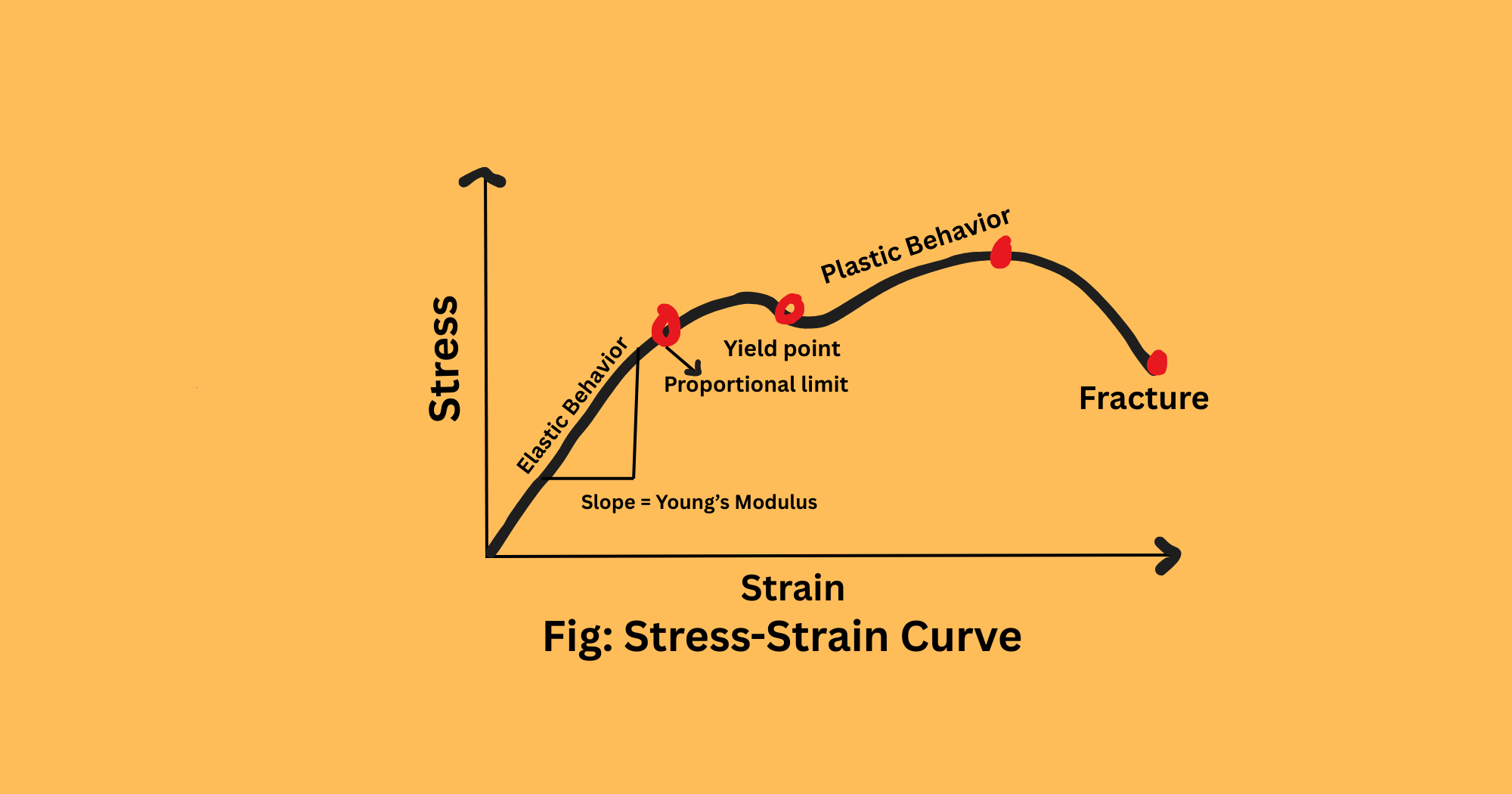

The graph plotted between the stress given and the strain produced is called a stress-strain curve. It is drawn to visually understand and study the effect of stress on an object. For the graph, strain is kept along the x-axis and stress is kept along the y-axis. The stress is kept gradually increasing. In the beginning we get a straight-line graph. Thus, we conclude that the strain produced by the stress also gradually increases. It goes according to Hooke’s law. The strain curve initially is a straight line. This straight-line part of the curve denotes the elasticity of the material. At this point stress and strain are directly proportional to each other and the point is called proportional limit.

When the stress is removed, the material can regain its shape up to this point. This maximum point up to which the material is elastic is called the elastic limit. Now, if the stress is increased further, the material starts showing plastic behavior. The deformation becomes permanent beyond this point in the graph.

Beyond the elastic limit lies the yield point. At this level of graph, it is easier to rapidly deform the object even with a small increase in stress. As stress continues to increase, the material finally comes to the point where it is unable to withstand the stress. This point is called the fracture point or breaking point. At this stage, the material eventually breaks.

These four points: proportional limit, elastic limit, yield point and fracture point determine the strength and elasticity of the material. Thus, it is an important tool to study the material’s behavior under stress.

Types of Elastic Moduli: Young’s, Shear, and Bulk Modulus

Elastic moduli are the quantities that measure elasticity of any material. The three main types of moduli are:

Young’s Modulus

Young’s modulus is the measure of elasticity material in one-dimension when the material is stretched or compressed. Mathematically, it is the ratio of longitudinal stress to longitudinal strain.

A material with a high Young’s modulus means the material is very stiff and does stretch much under stress. For example, steel. In contrast, a material with a low Young’s modulus stretches or compresses easily.

Shear Modulus

The shear modulus is the measure of the elasticity of a material when it is subjected to shear stress. A shear stress deforms the shape of a material without changing its volume. Mathematically, it is defined as the ratio of shear stress to shear strain. Greater shear modulus means the object is difficult to make a change in its shape.

Bulk Modulus

The bulk modulus is the measure of elasticity of a material when its volume is subjected to uniform stress from all sides. This makes a change in its volume. Mathematically, it is defined as the ratio of change in volume to the resulting decreased volume of the material.

By calculating bulk modulus, we can say how easily a material can be compressed in its volume. For example, liquids and solids have a high bulk modulus as compared to gas. Hence, gases are likely to compress more easily than solids and liquids.

Elastic Potential Energy: Stored Energy in Deformed Bodies

To deform a body elastically, some work is done on the body. This work done is stored as a potential energy in the body. This potential energy provides the restoring force after removing the deforming force and hence the potential energy is changed into the kinetic energy. It means the motion back to the initial state is done by this kinetic energy. Thus, elasticity comes from the potential energy of the material.

For a deforming elastic body, the elastic potential energy stored is given by,

Elastic Potential Energy = ½ k x² [Equation 3]

Here:

- k is the spring constant,

- x is the extension.

From equation (3) we see that the potential energy is directly proportional to the square of the displacement produced on the body.

Elastic potential energy can be very essential to gain restoring force and is very useful in certain daily life activities like vehicles, mechanical watches, bows and arrows etc. Hence it is the most important quantity to gain elasticity.

Poisson’s Ratio: Lateral vs. Longitudinal Strain

If a material is stretched or compressed in one direction, it becomes thinner in the perpendicular direction or thicker sideways. This effect of stress can be studied under Poisson’s ratio.

Poisson’s ratio (𝝂)

It is defined as the ratio of lateral strain to longitudinal strain. In simple words, it tells us how much a material changes its length or width in the direction perpendicular to the normal force. The value of Poisson’s ratio lies between 0 and 0.5. A small value means the material does not change much in width when stretched. A larger value means the width changes more noticeably. Thus, it is important to learn the changes occurred due to the stress along the axes while designing various structures, ensuring safety and minimizing losses.

Factors Affecting Elasticity: Temperature and Impurities

The elasticity of a material is also affected by several factors like temperature and impurities.

Effect of Temperature

As temperature increases, the materials are softened. Thus, a soft material cannot withstand much force. They can break easily and hence lose their elasticity. For example, a rubber pipe softens easily on heating and can be fitted into the pipelines. On the other hand, when temperature decreases, it automatically becomes tight.

Effect of Impurities

Adding impurities can both increase and decrease the elasticity of a material. For example, steels are made by adding small amount of carbon on iron. This makes the pure iron stronger and more elastic. Opposingly, rust damages iron and makes it weaker.

Real-World Applications: Elasticity in Engineering and Materials Science

- In Construction and Architecture

Bridges, buildings, and towers are huge constructions which are often deformed by winds or natural disasters. Hence, to make them strong enough to withstand the force, they are designed with special materials like rods so that they can deform elastically under these forces. They can return to their original shape when the force is removed and become safer unless the force is huge.

- In Vehicles and Machines

In rough or gravel roads, vehicles often experience bumps and bounce. Hence, to regain their position after the bumps, vehicles are assigned with shock absorbers. This makes driving more comfortable with safety.

- In Medical Science

Elastic materials are used in prosthetics, braces, and medical devices. The elastic properties of tissues are also important in understanding how the human body moves and how organs respond to forces.

- In Everyday Objects

Rubber bands, mattresses, balls, shoes, and even clothes depend on elastic behavior. Without elasticity, many everyday objects would not work properly or would break easily.

- In Materials Science

Scientists study elasticity to develop new materials that are stronger, lighter, and more flexible. These materials are used in airplanes, spacecraft, sports equipment, and modern technology.

Thus, elasticity is a key concept that connects physics to real-world design and innovation.

Conclusion

Elasticity is a natural property of material that describes its strength to overcome the deforming force. This property lies under Hooke’s law, and every material has an elastic limit for the case the force is not too large. Hence, it helps to know the behavior of a material under different forces. Also, a hard or stiff material has greater restoring force and is elastic in nature.

Through concepts like Hooke’s Law, stress-strain curves, and elastic moduli, we gain a clear picture of the nature of materials, and to which limit they can resist forces. Moreover, the concept of potential energy and Poisson’s ratio add to our understanding of the potential energy stored by a material.

Elasticity is also affected by factors like temperature and impurities. Hence, it is not a fixed value and changes upon various environmental conditions. Various applications are based on this property. From engineering, construction, medicine to everyday life, we are directly impacted by elasticity.

To sum up, elasticity helps us to design safer structures and vehicles and also to design useful material in material science and engineering. It has remained as the foundation of several natural to complex technological phenomena.

References

Williams, E. (1956). Hooke’s Law and the Concept of the Elastic Limit. Annals of Science, 12(1), 74-83.

Giuliodori, M. J., Lujan, H. L., Briggs, W. S., Palani, G., & DiCarlo, S. E. (2009). Hooke’s law: applications of a recurring principle. Advances in physiology education, 33(4), 293-296.

Hooke’s Law: Statement, Formula, and Diagram

Thompson, J. O. (1926). Hooke’s law. Science, 64(1656), 298-299.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elasticity_(physics)

https://byjus.com/jee/elasticity