The fundamental concepts of gene expression were based on genetic analysis of bacteria and viruses (prokaryotes only). The development of gene cloning, or molecular cloning, allowed scientists and molecular biologists to manipulate genes for any cell type, thus enabling scrutinized studies of eukaryotic genes and progressing the understanding of cell biology.

Gene cloning, also referred to as DNA cloning or molecular cloning, is a fundamental concept of recombinant DNA technology (RDT) in molecular biology in which fragments of nucleic acid (DNA or RNA) are made into multiple copies using sophisticated techniques of genetic engineering. rDNA is formed only when DNA fragments from different species or sources are joined together. Therefore, gene cloning, the process of making multiple copies of DNA, doesn’t necessarily mean mixing DNA from different species. For example, PCR can amplify a gene in vitro without the formation of rDNA. These particular fragments or specific sequences of nucleic acids that are to be cloned are called the target DNA or gene of interest (GOI).

Principles of Recombinant DNA Technology

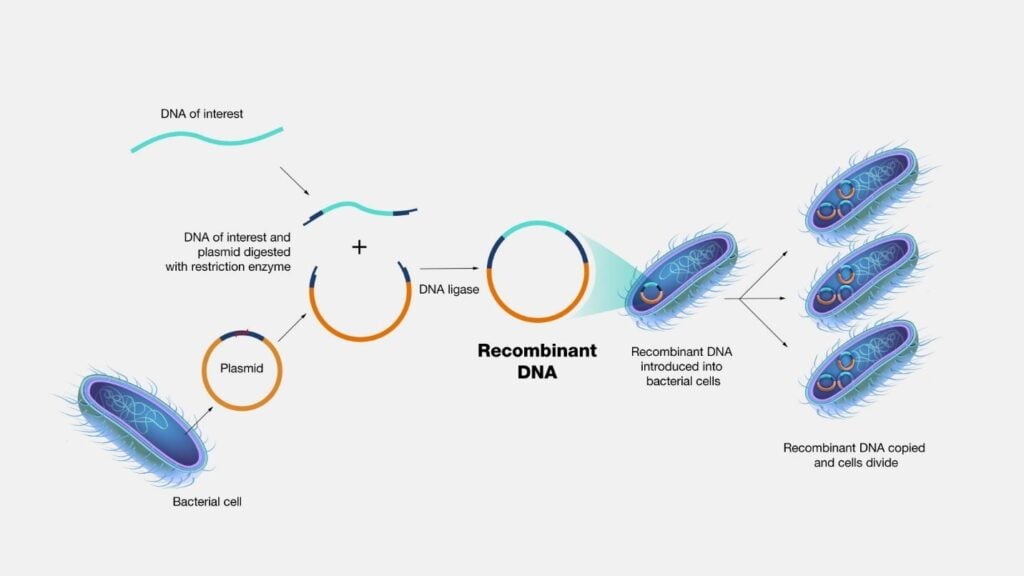

The core idea of recombinant DNA technology is the combination of two or more genetic materials into a single genetic material and the formation of multiple copies of the target gene. The basic principle in gene cloning is to combine a gene of interest into another DNA molecule, which is capable of independent replication inside a host.

Restriction enzymes cleave the GOI from the donor cell. The extracted GOI is combined with the genome of a vector artificially (in-vitro conditions) using special ligation enzymes. This combined genome of the donor organism and vector is now called a recombinant DNA. The recombinant DNA is then inserted into a host. The multiplication of target DNA along with the host occurs, by which multiple copies of the gene of interest are formed. Generally, bacteria are used as hosts or recipients in gene cloning due to their ability to efficiently express foreign DNA.

Source: https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Recombinant-DNA-Technology

Isolation of Genetic Material

The pilot step in RDT is the isolation of the desired gene from the host. Firstly, the total DNA or mRNA of the host needs to be extracted. DNA/RNA extractions are generally performed using kit-based or organic precipitation methods.

If the total gene sequence of an organism is unknown, the whole genome is first processed to produce a genome library and hence sequenced. Then, the target gene is identified by bioinformatics tools using the sequence.

Similarly, if sequences of the gene of interest are available, a specific gene of interest (from genomic DNA or mRNA) for cloning can be prepared using:

PCR: Among the total extracted DNA, a high number of copies of the gene of interest can be obtained by PCR using gene-specific primers, which can amplify only the target DNA. In this case, gene cloning does not involve RDT, as the gene of interest, which needs to be amplified, is not inserted into a vector for multiplication.

Restriction endonuclease: A special enzyme called a restriction endonuclease, which cleaves off specific segments of a gene, can be used to selectively extract the gene of interest from the total DNA.

Reverse transcription: The extracted mRNA can be reverse transcribed to form complementary DNA (cDNA) by reverse transcription (RT-PCR).

All these preparation procedures for preparing GOI necessary for cloning demand high-quality, contaminant-free nucleic acids, as impurities can interfere with the involved enzymes and hinder their functions.

Enzymes Used in Cloning

Various enzymes are necessary during gene cloning, such as:

- Restriction Endonuclease (REs)

Restriction endonucleases (Res) are among the most important enzymes in RDT. Also called “molecular scissors”, restriction endonuclease recognizes specific sequences in a gene and cleaves at exactly or close to the recognition sequence. These specific sites are called restriction sites.

In contrast to exonucleases, which cleave nucleotides from the terminal position, REs can initiate the breakage of the phosphodiester bond in the middle of the DNA strand, called restriction digestion. Restriction digestion produces either sticky or blunt ends. REs cleaves DNA from both the donor cell and the vector. EcoRI, HindIII, and SmaI are among the commonly used restriction endonucleases.

Source: https://nordicbiosite.com/blog/restriction-enzymes-101

- DNA Ligase

DNA ligases bind the 5’ phosphate and 3’ hydroxyl ends of DNA fragments, which form a strong phosphodiester bond and hence create a continuous double-stranded DNA. DNA from the vector and donor cell is linked by DNA ligase. These ligases use ATP or NAD as an energy source during ligation. A bacteriophage-derived ligase, T4 DNA ligase, is commonly used for ligating vector and target DNA.

- DNA polymerase

In the case of PCR cloning, PCR-generated DNA fragments are directly ligated onto the vector. Here, Taq DNA polymerases add adenosine molecules at the 3’ end, using specially designed primers, generating polyA sites. These polyA sites can be directly ligated with T-tailed vectors, also called TA cloning. As Taq DNA polymerase doesn’t have a proofreading ability, high-fidelity DNA polymerases such as Pfu polymerase are preferred during TA cloning to minimize errors and mutations and ensure high accuracy during PCR.

- Alkaline Phosphatase

Alkaline phosphatases are enzymes that can remove phosphate groups from 5’ ends of nucleic acids. During cloning, after the action of endonucleases, vectors often tend to rejoin with themselves, rather than the target DNA. Alkaline phosphatases remove the 5’ phosphate ends so that the dephosphorylated end of the vector cannot rebind with itself. When a target DNA appears to bind, it provides the necessary phosphate, ensuring ligation with only the intended DNA sequence, not itself.

- Reverse Transcriptase (RT)

The enzyme reverse transcriptase converts messenger RNA (mRNA) into complementary DNA (cDNA).

For example, when a eukaryotic protein needs to be expressed in prokaryotes, prokaryotes cannot remove or slice introns (non-coding sequences). As non-coding sequences (introns) are not expressed into mRNA, prokaryotic hosts, such as bacteria, can correctly express eukaryotic proteins without the need to splice out introns. Reverse transcriptase converts mRNA, which is formed from exons only (protein-coding sequences), into cDNA such that prokaryotic hosts can correctly express eukaryotic proteins, without the need to splice out introns.

Therefore, RT converts mRNA into cDNA for cloning expressed genes.

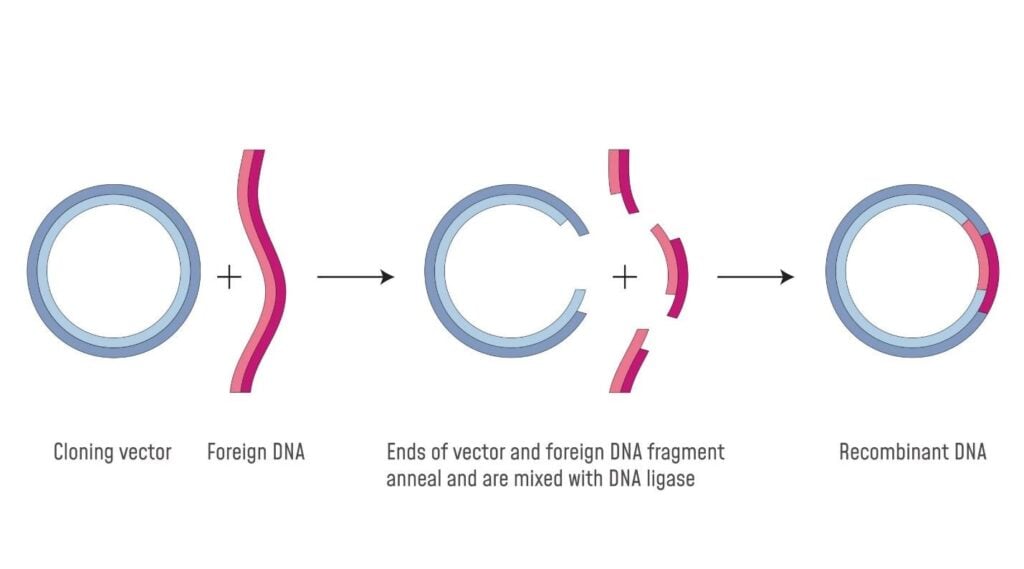

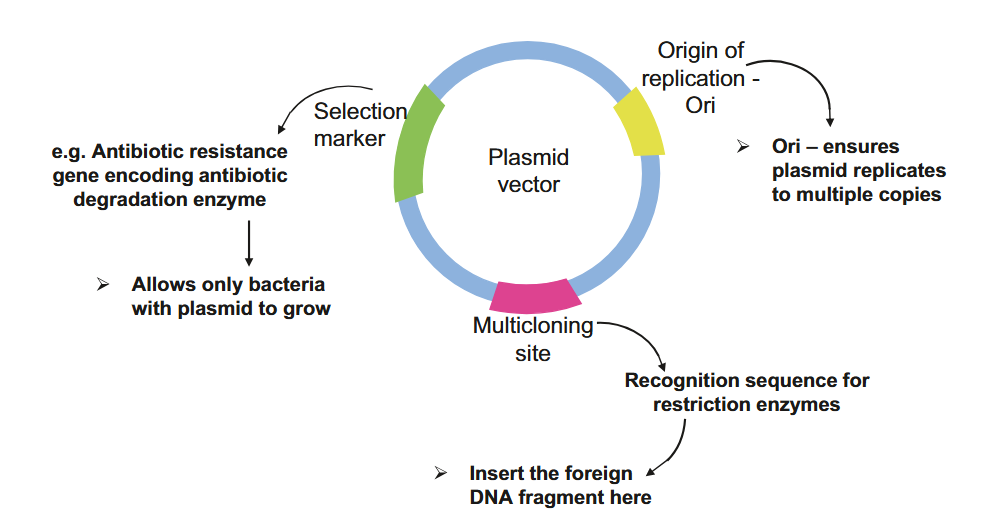

Cloning Vectors

For gene cloning, a cloning vector is required. Vectors are carriers of foreign DNA fragments that carry certain foreign DNA into the host cell and replicate along with the host. The gene of interest becomes an integral part of the vector as it associates and joins with the vector by phosphodiester bonds. Generally, plasmids are presented as vectors into the host.

Types of cloning vectors: Prokaryotic vectors: Plasmids, Cosmids, Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs)

- Eukaryotic vectors: Yeast artificial chromosomes (YACs), Human Artificial Chromosome (HAC)

- Viral vectors: Adenoviral vector, Lentiviral Vector, Bacteriophages,

Prerequisites to be a good vector:

- Able to carry foreign DNA into the host

- Easy to isolate and purify

- Transferable to host

- Autonomous replication in a host with Origin of Replication (Ori) site

- Contain recognition sites for restriction endonucleases

- Contain a marker gene to allow the selection of transformed cells (Selection Marker)

- Small Size

- Stable in the host

Source: Patil R., Sivaram A., Patil N. In: A complete guide to gene cloning: from basic to advanced. Patil N., Sivaram A., editors. Springer; Cham, Switzerland: 2022. Gene isolation methods: beginner’s guide

Ligation of DNA Fragments

Ligation, in molecular biology, refers to the joining of DNA fragments by the enzyme DNA ligase by creating a covalent linkage at the 3’ hydroxyl and 5’ phosphate ends of the DNA fragments. The compatible DNA of both the vector and the donor cell, produced after the action of restriction endonucleases, is ligated together.

Phosphodiester bonds form between a vector and a DNA fragment, resulting in a rDNA molecule containing both the gene of interest and vector DNA. Generally, a ligation reaction involves the incubation of the vector and the target DNA along with the enzyme DNA ligase (normally T4 DNA ligase) and an ATP-containing buffer. T4 DNA ligases can effectively join both the sticky and blunt ends. After ligation, the rDNA is competent for transformation into a host for multiplication.

Transformation Techniques / Techniques of rDNA Transfer:

Various Physical, Chemical and Biological methods are employed for the delivery of the gene of interest into a host cell for multiplication.

Physical Methods: It involves direct DNA transfer into the cytoplasm or nucleus of the host cells through a physical force that delivers DNA into the host, without the need for chemical or biological processes. Microneedle Injections, Biolistic Gene transfer, Electroporation, Sonoporation, Optoporation, Magnetofection, etc., are some of the physical methods.

Chemical Methods: It involves DNA transfer using chemicals to directly facilitate the uptake of foreign DNA into cells by enhancing endocytosis or disrupting the cell membrane. Techniques such as Calcium phosphate precipitation, Liposome-based transfer, and polymeric carrier-based transfer are the chemical methods used for gene transfer.

Biological Methods: It involves using biological agents such as bacteria and viruses to deliver DNA into host cells. Protoplast Fusion, Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer, and viral vector-mediated gene transfer are some of the key biological techniques used for gene transfer.

Selection and Screening Methods of Recombinants

Distinguishing transformed cells (rDNA with vector) from the non-transformed cells (no vector) is necessary. For example, most commonly used plasmid vectors consist of ampicillin-resistant genes. Bacterial cells transformed with this vector survive on media containing ampicillin due to the presence of resistant genes in the plasmid. Cells without the vector do not survive due to the absence of the antibiotic-resistant gene. Therefore, the trait expressed by the vector distinguishes desired recombinants from non-recombinants.

To confirm accuracy in recombination, high-throughput techniques such as hybridization of the gene of interest with fluorescent or radio-labelled probes, by blue-white screening, sequencing, or immunological tests are also applied.

Applications in Medicine and Agriculture

Medicine and Healthcare

- Vaccine Development: Recombinant vaccines against infectious diseases such as polio, tetanus, measles, hepatitis, etc., carry specific proteins developed through rDNA technology, which develop antibody-mediated immunity against the pathogens.

- Therapeutic Protein Development: Synthesis of several therapeutic proteins, such as Human Insulin, Human Growth Hormone, Monoclonal antibodies, Interferons, Antibiotics, and antitumor agents have been accomplished by cloning genes coding these proteins in alternate hosts.

- Molecular diagnostics: RDT allows screening for various diseases, which helps in the identification of mutations and genes related to a particular disease, therefore enabling faster treatment.

- Gene therapy: It involves the repair or reconstruction of defective genetic materials. Newer technologies, such as TALENs, CRISPR, and zinc finger nucleases, are common RDT-based systems for personalized medicine and gene therapy.

Agriculture

- Nutritional enhancement of crops: Genetic modification of food to create a better nutritional profile. Rice, for example, does not contain vitamin A. A genetically engineered strain of rice, Golden Rice, contains the gene for phytoene synthase, which makes it rich in vitamin A or β-carotene, enhancing its nutritional value.

- Resistance to Herbicides and Pests: Crops such as Bt Cotton, B.T. Maize, and B.T. Brinjal contains genes from Bacillus thuringiensis to produce toxins that kill pests. This reduces the need for insecticides and pests.

- Abiotic stress tolerance: Field and fruit crops are engineered to withstand extreme environmental stresses like drought, salinity, and extreme temperature through RDT.

- Improved Crop Yield: Crops such as Flavr Savr tomatoes have better shelf life, as their ripening process is slowed down by inhibition of polygalacturonase, which acts to accelerate fruit ripening.

Ethical and Safety Considerations

- Genetically Modified Organism (GMO), if released in the environment, can lead to ecological disasters and affect human and animal welfare. For example, genetically engineered bacteria containing antibiotic-resistant genes could lead to the genetic transfer of these resistant genes to natural bacterial populations, worsening the problem of antimicrobial resistance.

- Recombinant products could lead to unnatural side effects, including but not limited to immune reactions, cytotoxicity, and mutations. For example, early gene therapy using retroviral vectors caused leukemia among some patients.

- Genetic changes in humans raise ethical concerns about consent, identity, genetic enhancement, and misuse for non-therapeutic purposes.

- Extensive cultivation of transgenic crops could lead to the emergence of resistance to pesticides, affecting biodiversity and creating an imbalance in the ecosystem.

Conclusion

Molecular cloning and recombinant DNA technology have effectively structured modern-day molecular biology by precise genetic manipulation and production of valuable biological products. The application of RDT in medicine, research, agriculture, and various other sectors improves human health and scientific understanding day-by-day. However, these technologies raise important ethical and moral concerns, which must be addressed carefully. Only by responsible regulation and ethical awareness can RDT continue to be a vital tool for the benefit of all.

References

Hong, W., Ha, S. G., Kwon, H. C., & Lee, S. V. (2025). Brief guide to gene cloning. Molecules and cells, 48(8), 100234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mocell.2025.100234

Cooper GM. The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd edition. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2000. Recombinant DNA. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9950/

Hammadi AA, Al-Mousawi MRR, “Cloning of DNA: A Review”. Sci. J. Med. Res. 2021;5(20):130-134. DOI: 10.37623/sjomr.v05i20.7

Patil R., Sivaram A., Patil N. In: A complete guide to gene cloning: from basic to advanced. Patil N., Sivaram A., editors. Springer; Cham, Switzerland: 2022. Gene isolation methods: beginner’s guide

Tabor S. (2001). DNA ligases. Current protocols in molecular biology, Chapter 3, Unit3.14. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142727.mb0314s08

https://ijarbs.com/pdfcopy/2022/mar2022/ijarbs16.pdf

https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.1001916