- Herpes Simplex Virus-1 (HSV-1) is a ubiquitous, neurotropic, enveloped, linear, and double-stranded DNA virus of 152 Kb in size and belongs to the family Alphaherpesvirinae.

- Global seroprevalence is extremely high: ~3.7 billion people <50 years (~67%) are infected with HSV 1.

- Typically acquired as a child through orofacial contact; infections are generally asymptomatic; however, HSV-1 causes serious disease in neonates, immunocompromised persons, and CNS and ocular infections.

- Hallmark features include:

- Lytic replication in epithelial and mucosal cells

- Lifelong latency of sensory neurons (e.g., trigeminal ganglia) with periodic reactivation and shedding

- Sophisticated immune evasion.

Therefore, HSV 1 can be seen as an important public health problem as well as a paradigm for latency, immune evasion, and neurotropism.

Taxonomy and Classification of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1)

- Family: Herpesviridae

- Subfamily: Alphaherpesvirinae

- Genus: Simplexvirus

- Species: Human alphaherpesvirus 1 (HSV-1).

- Alphaherpesviruses share:

- Short replication cycle in permissive cells

- Broad host and cell tropism

- Capacity for lifelong latency in sensory neurons.

- Closely related species:

- HSV-2 (Human alphaherpesvirus 2), more commonly genital but with increasing overlap in anatomic tropism.

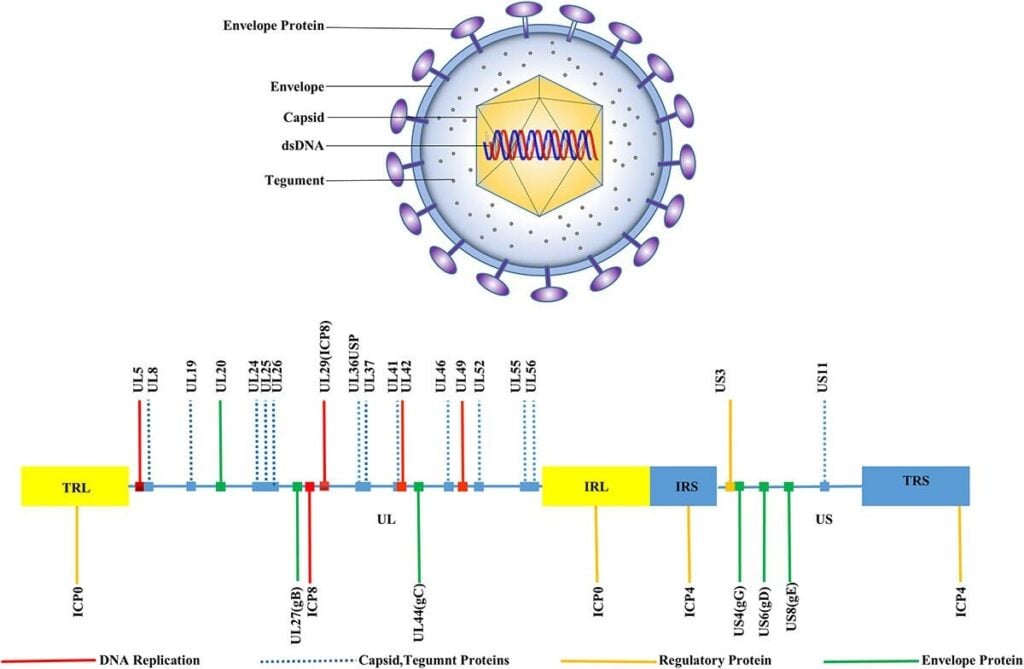

Structure and Morphology of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1)

Fig:1. HSV-1 structure, Morphology, and genomic organization (Su et al., 2024)

- HSV-1 virion is a large, enveloped icosahedral particle comprising four major components:

- Linear dsDNA genome (~152 kb)

- Icosahedral capsid (T=16) with 162 capsomeres, ~100–110 nm in diameter.

- Tegument: The tegument consists of 20-23 distinct viral periplasmic proteins surrounding the capsid, which are structural and rich in regulatory proteins (e.g., VP16, UL36, VP22); involving in transcriptional activation, transport, and immune evasion.

- Lipid envelope: There are 12 envelope glycoproteins (gB, gC, gD, gE, gG, gH, gI, gJ, gK, gL, gM, and gN) mediating attachment, entry, cell-to-cell spread, and immune modulation.

Key structural features:

- gB, gD, gH/gL form the core fusion machinery; gC, gB bind heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs); gD binds entry receptors (e.g., nectin-1, HVEM).

- gE/gI act as an Fc receptor and contribute to immune evasion and neuroinvasion.

- Tegument proteins deliver pre-formed viral regulators into the host cell immediately upon entry, ensuring rapid commandeering of host machinery.

Genome Organization and Proteins of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1)

- Genome type: Linear, double-stranded DNA, ~152–153 kb

- GC-rich (~68% G+C)

- Isomeric forms:

- Two unique regions: UL (unique long), ~82% of genome; US (unique short), ~18%

- Each flanked by inverted repeats:

- TRL – UL – IRL – IRS – US – TRS (terminal and internal repeats of L and S)

- Homologous sequences mediate inversion, giving four equimolar genome isomers

- Modern View: Expanded Coding Capacity

- 201 viral transcripts and 284 ORFs (including all known plus 46 new large ORFs).

- Extensive transcript isoform diversity at most loci.

- Widespread upstream ORFs (uORFs) and upstream overlapping ORFs (uoORFs).

- Many N-terminal extensions (NTEs) and N-terminal truncations (NTTs) of known proteins, often from non-canonical start codons.

- Temporal Classes of HSV-1 Genes

Immediate-early (α): ICP0 (RL2), ICP4 (RS1), ICP22 (US1), ICP27 (UL54), ICP47 (US12) – transcriptional and immune regulators

Early (β): DNA replication machinery (UL9, UL29, UL30, UL42, UL5/UL8/UL52, etc.) and nucleotide metabolism.

Leaky-late (γ1) & true late (γ2):

- Structural capsid proteins (UL19/VP5, UL35/VP26, UL38/VP19C, UL25, UL37)

- Tegument proteins (UL21, UL36, UL41, UL46–UL49, US2, US10, US11, US9)

- Glycoproteins (UL27/gB, UL44/gC, UL1/gL, UL10/gM, UL49A/gN, US4/gG, US5/gJ, US6/gD, US7/gI, US8/gE)

- Replication proteins

- UL9: origin-binding helicase–like protein.

- UL30/UL42: DNA polymerase/processivity factor.

- UL5/UL8/UL52: three-component helicase/primase complex

- UL29 (ICP8): ssDNA-binding protein.

- Major capsid proteins:

- UL19 (VP5/ICP5), UL35 (VP26), UL38 (VP19C), UL18, UL25, UL36, UL37

- Portal and terminase complex:

- UL6: dodecameric portal at one vertex.

- UL15, UL28, UL33: terminase that cleaves concatemers and packages DNA

- UL17 & UL25: capsid vertex-specific component (CVSC)

- UL32: portal-associated factor

- Tegument Protein Coding Regions

- VP16 (UL48): tegument transactivator of IE genes; multiple NTE forms with distinct packaging and localization

- VP22 (UL49): modulates cytoskeleton, virion assembly; bridges gE/gI/gM and recruits ICP0

- UL36/UL37: inner tegument, capsid transport.

- UL41 (vhs): RNase that degrades host mRNAs (virion host shutoff)

- US10, US11, US2, US9: additional tegument proteins involved in RNA binding, immune modulation, and axonal transport

DNA Replication Proteins and Replisome Organization of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1)

- UL9: origin-binding; initiates unwinding at oriL/oriS.

- UL5/UL8/UL52: three-component helicase–primase complex:

- UL5: 5′–3′ helicase.

- UL52: primase that synthesizes RNA primers.

- UL8: non-catalytic subunit coordinating helicase/primase with fork progression (Bermek & Williams, 2021).

- UL30 (Pol) + UL42: polymerase and clamp-like processivity factor, analogous to cellular Pol δ/PCNA systems (Lehman & Boehmer, 1999).

- UL29 (ICP8): ssDNA binding protein; organizes replication compartments.

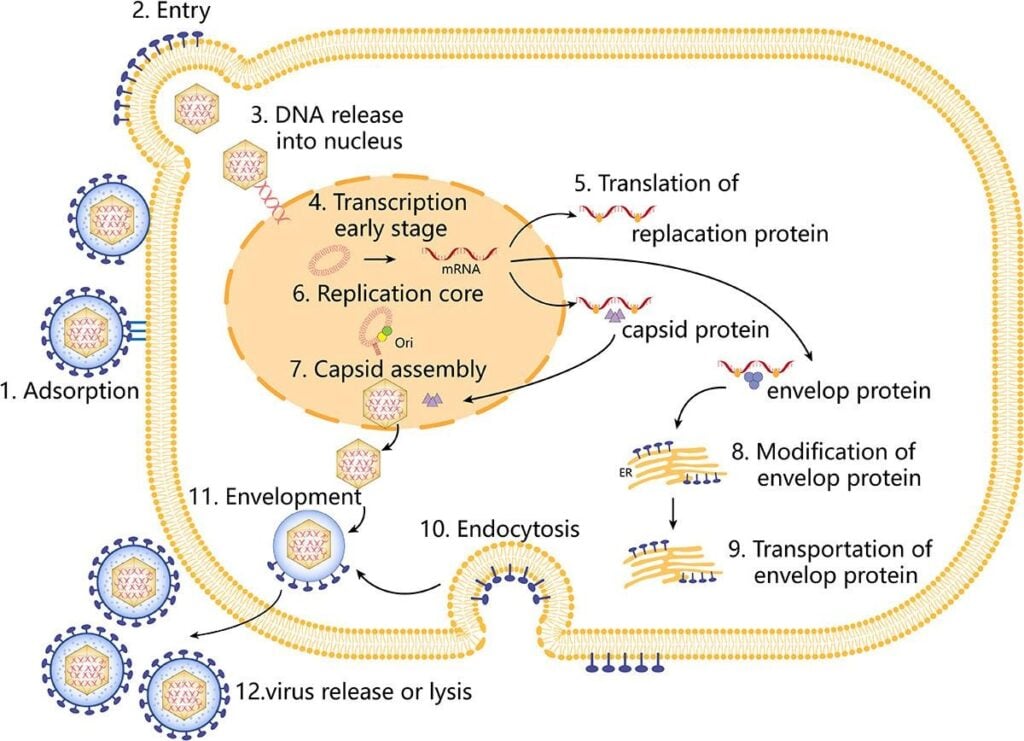

Replication Cycle of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1)

Key stages of the lytic cycle in epithelial or other permissive cells:

Fig 2: Replication cycle of HSV-1 (Su et al., 2024)

- Attachment and entry

- Initial binding via gB/gC to heparan sulfate on host cell surfaces, followed by gD engagement of specific entry receptors (nectin-1, HVEM, 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate).

- Fusion of the viral envelope with plasma or endosomal membranes mediated by gB and gH/gL.

- Delivery of capsid plus tegument into cytoplasm, microtubule-dependent transport to the nuclear pore.

- Nuclear entry and gene expression

- Viral DNA is injected into the nucleus through the nuclear pore.

- Sequential transcription:

- IE genes (α) activated by tegument protein VP16 in complex with host factors.

- IE proteins (notably ICP4, ICP27) drive early (β) gene transcription.

- Early proteins mediate DNA replication; late (γ) genes are then expressed for structural components.

- DNA replication

- Origin-dependent initiation at oriL and oriS, conversion to rolling-circle replication, and formation of concatemers.

- Assembly and egress

- Capsid assembly in the nucleus, packaging of unit-length genomes via the portal complex.

- Primary envelopment at the inner nuclear membrane and de-envelopment at the outer membrane; tegument acquisition and secondary envelopment at trans-Golgi or endosomal membranes.

- Egress by exocytosis and cell-to-cell spread via junctional complexes.

- Latency and reactivation

- Following primary mucosal infection, virions infect sensory nerve terminals and are retrogradely transported to ganglia (e.g., trigeminal, sacral).

- In neurons:

- Circularization of viral DNA, predominant LAT expression, and extensive heterochromatinization of lytic gene promoters.

- No infectious virion production in true latency.

- Reactivation triggered by stressors (UV light, fever, trauma, immunosuppression), leading to anterograde transport of virions to peripheral sites and recurrent lesions.

Pathogenesis and Host Immune Response of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1)

- Pathogenesis involves:

- Lytic destruction of epithelial or other target cells (skin, cornea, CNS).

- Neuronal infection and latency with periodic viral shedding, often asymptomatic.

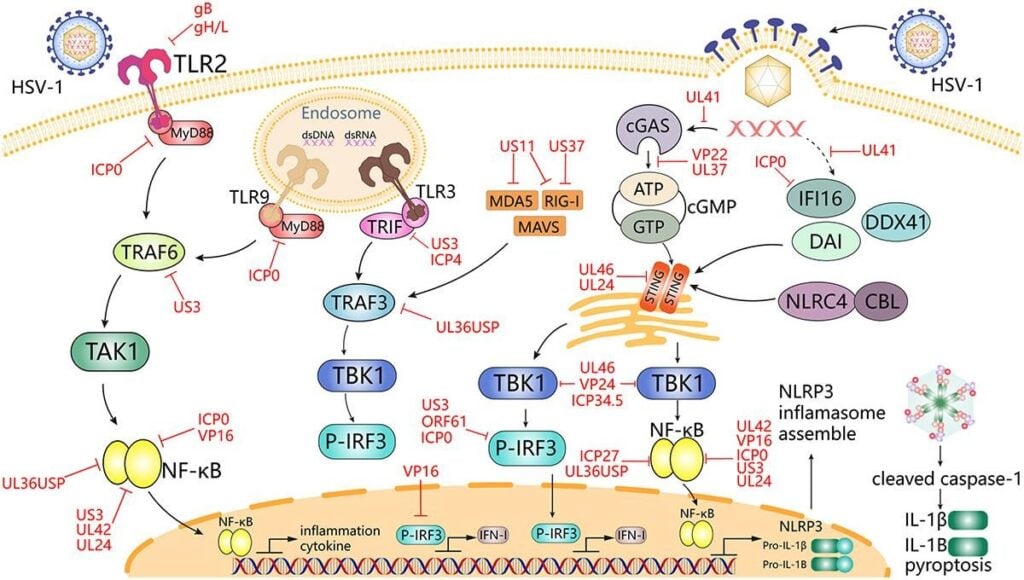

- Innate immune responses:

- Pattern recognition receptors (e.g., TLR2, TLR3, cGAS-STING, RIG-I-like receptors) detect HSV-1 nucleic acids.

- Induction of type I and III interferons, pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF, IL-1β, IL-6), and chemokines.

- NK cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and epithelial cells contribute to early containment.

- Adaptive immunity:

- CD4⁺ T cells provide help and secrete IFN-γ; CD8⁺ cytotoxic T cells kill infected cells and contribute to control of latency/reactivation in ganglia.

- Neutralizing antibodies to glycoproteins (especially gB, gD) limit spread but do not eradicate latent virus.

- Immune evasion strategies (selected examples):

- ICP47 blocks TAP-mediated peptide transport, impairing MHC-I antigen presentation.

- UL41 (vhs) degrades host mRNA, dampening antiviral gene expression.

- US3 and other kinases inhibit apoptosis and interferon signaling.

- gE/gI acts as an Fc receptor, interfering with antibody-mediated effector mechanisms.

- Interference with cGAS-STING, TBK1, IRF3 pathways attenuates IFN production.

Immunopathology contributes importantly to herpes stromal keratitis and herpes encephalitis, where host responses drive tissue damage in addition to direct cytopathic effects.

Fig 3: HSV-1 mediates innate immune signaling and escape strategies (Su et al., 2024)

Epidemiology and Transmission of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1)

- Burden:

- ~3.7 billion people under 50 years infected with HSV-1 globally; adult seroprevalence often >80%.

- Seroprevalence is inversely associated with socioeconomic status, with earlier acquisition in low-income settings.

- Trends and risk groups:

- Shift toward HSV-1 as a major cause of genital herpes in many high-income countries, particularly among young adults.

- Increased recognition of neonatal HSV-1 infections and late-onset disease associated with genital HSV-1 in mothers.

- Transmission routes:

- Direct contact with infected secretions or lesions (saliva, orolabial contact, genital contact).

- Oral–oral and oral–genital routes are dominant for HSV-1.

- Asymptomatic shedding from oral, nasal, and ocular mucosa is frequent and underlies much of transmission.

- Perinatal transmission during vaginal delivery from genital HSV-1 infection.

- Risk factors for HIV transmission include HSV 1 infection, which has a high risk when it is a genital herpes infection. There is epidemiological association with some cancers, as well as neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Clinical Manifestations of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1)

- Spectrum ranges from asymptomatic to life-threatening:

- Orofacial disease

- Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis in children: painful vesicles/ulcers occur on the oral mucosa, tongue, palate, and gingiva, fever, lymphadenopathy.

- Recurrent herpes labialis (“cold sores”): vesiculo-ulcerative lesions at the mucocutaneous junctions around lips; often preceded by prodrome (tingling, burning).

- Herpetic sycosis, herpes gladiatorum, and herpetic whitlow in specific exposure scenarios (barbers, wrestlers, healthcare workers).

- Ocular HSV-1

- Blepharoconjunctivitis, epithelial keratitis, stromal keratitis, endotheliitis, uveitis. Whereas, HSV keratitis is a leading cause of infectious corneal blindness in developed countries.

- Genital HSV-1

- Most common; genital ulcers, dysuria, systemic symptoms similar to HSV-2, with notable asymptomatic shedding.

- Central nervous system disease

- Herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE): focal, often temporal-lobe encephalitis with fever, altered mental status, seizures; high morbidity/mortality without prompt acyclovir.

- Meningitis, myelitis, and rarely HSV-associated neurocognitive syndromes; experimental and epidemiologic data link HSV-1 to Alzheimer-‘s-like pathology.

- Neonatal HSV-1

- Localized skin/eye/mouth disease, CNS disease, or disseminated infection, including hepatitis, pneumonia, coagulopathy; high risk for death or sequelae without therapy.

- Disease in immunocompromised hosts

- Chronic, atypical, or deep tissue ulcers, disseminated infection, pneumonia, extensive mucocutaneous disease; higher rates of antiviral resistance.

Laboratory Diagnosis of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1)

- Direct detection methods:

- Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs, particularly real-time PCR) from vesicle swabs, CSF, corneal scrapings, or other samples:

- High sensitivity and specificity

- Standard of care for HSE (CSF PCR) and ocular HSV.

- Viral culture:

- Historically gold standard for mucocutaneous disease; allows susceptibility testing, but is less sensitive than PCR and slower.

- Antigen detection (DFA) and cytology (Tzanck smear) have largely been superseded by PCR due to lower sensitivity and specificity, but may still be used in some settings.

- Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs, particularly real-time PCR) from vesicle swabs, CSF, corneal scrapings, or other samples:

- Serology:

Type-specific IgG to gG-1/gG-2 for epidemiologic studies or to distinguish primary acquisition vs reactivation; not useful for acute lesion diagnosis given high background seroprevalence.

- Typing

Molecular methods (PCR with type-specific primers, sequencing) distinguish HSV-1 from HSV-2, which is critical for prognosis, counseling, and epidemiology.

- Antiviral resistance testing

Phenotypic assays or genotypic detection of mutations in UL23 (thymidine kinase) and UL30 (DNA polymerase) for refractory disease, especially in immunocompromised patients.

Treatment and Antiviral Therapy of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1)

- Current standard therapies target viral DNA polymerase and require phosphorylation by viral thymidine kinase (for nucleoside analogues):

- Approved drugs

- Acyclovir (ACV), valacyclovir, famciclovir (prodrug of penciclovir):

- Competitive substrates for viral DNA polymerase, causing chain termination or slowed elongation.

- Effective for mucocutaneous disease, genital herpes, HSE, neonatal HSV, and keratitis (with topical formulations).

- Long-term suppressive therapy reduces recurrence and shedding but does not clear the latent virus.

- Foscarnet and cidofovir:

- Direct polymerase inhibitors not requiring TK activation.

- Used as rescue therapy for ACV-resistant HSV-1, but limited by nephrotoxicity and other adverse effects.

- Acyclovir (ACV), valacyclovir, famciclovir (prodrug of penciclovir):

- Limitations

- No current drug eradicates latency; recurrences continue after cessation.

- Resistance, particularly TK-deficient or altered TK mutants, is problematic in heavily immunosuppressed populations.

- Emerging therapies

- Helicase-primase inhibitors (HPIs) (e.g., pritelivir, amenamevir):

- Target UL5/UL8/UL52 helicase-primase complex, independent of TK, active against ACV-resistant strains, with potent suppression of shedding and recurrences in trials.

- Host-targeted strategies:

- Target host factors critical for HSV replication or immune evasion (e.g., cellular kinases, entry receptors, autophagy pathways).

- Gene-based approaches:

- CRISPR/Cas or other genome editing strategies aimed at latent genomes; still an early-stage.

- Helicase-primase inhibitors (HPIs) (e.g., pritelivir, amenamevir):

Prevention and Control of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1)

- General measures:

- Avoidance of direct contact with active lesions, hand hygiene, and use of barriers in healthcare settings.

- Counseling regarding asymptomatic shedding and transmission risks, especially for oral, genital, and perinatal transmission.

- In neonates and pregnant women, screening for a history of genital herpes, a cesarean delivery for active genital lesions during labor, and suppressive therapy during late pregnancy when indicated.

- Pharmacologic prophylaxis

- Long-term suppressive acyclovir/valacyclovir in patients with frequent recurrences, ocular disease, or in some immunocompromised hosts to reduce episodes and shedding.

- Vaccines

To date, no licensed prophylactic or therapeutic HSV-1/HSV-2 vaccine despite >70 years of research.

- Candidates under investigation include:

- gD or multivalent glycoprotein subunit vaccines

- Live-attenuated and replication-defective vectors

- DNA/RNA vaccines and HSV-based vectors with engineered attenuation.

- Limited efficacy in past trials has driven exploration of novel antigens, adjuvants, and strategies targeting both humoral and robust tissue-resident T-cell responses.

- HSV-1 as a tool

Engineered HSV-1 vectors have been utilized for oncolytic virotherapy, gene therapy, and tracing neural circuits, taking advantage of their large genetic capacity, neurotropism, and modifiable virulence.

Conclusion

HSV 1 is a human pathogen characterized by high global prevalence, lifelong neuronal latency, episodic reactivation, and substantial clinical heterogeneity. Its large, complex genome underpins sophisticated manipulation of host cell biology and immune evasion, ensuring persistence despite robust innate and adaptive responses. While nucleoside analogue therapy has transformed outcomes for acute disease, notably HSE and neonatal infection, failure to eliminate latent virus, acquisition of resistance in high-risk groups, and the absence of an effective vaccine remain abiding challenges. Continued dissection of HSV-1 structure, gene function, host interactions, and immune correlates of protection will provide a necessary framework for guiding the next generation of antivirals, vaccines, and vector-based therapeutics.

References

- Arduino, P. G., & Porter, S. R. (2008). Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 infection: Overview on relevant clinico-pathological features. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine, 37(2), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00586.x

- Bai, L., Xu, J., Zeng, L., Zhang, L., & Zhou, F. (2024). A review of HSV pathogenesis, vaccine development, and advanced applications. Molecular Biomedicine, 5, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43556-024-00177-3

- Birkmann, A., & Saunders, R. (2025). Overview on the management of herpes simplex virus infections: Current therapies and future directions. Antiviral Research, 225, 105560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2024.105560

- Denes, C. E., Everett, R. D., & Diefenbach, R. J. (2019). Tour de herpes: Cycling through the life and biology of HSV-1. In R. J. Diefenbach & C. Fraefel (Eds.), Herpes Simplex Virus: Methods and Protocols (pp. 1–27). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-9554-7_1

- Hussain, M. T., Stanfield, B. A., & Bernstein, D. I. (2024). Small animal models to study herpes simplex virus infections. Viruses, 16(7), 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/v16071134

- Koganti, R., Yadavalli, T., & Shukla, D. (2019). Current and emerging therapies for ocular herpes simplex virus type-1 infections. Microorganisms, 7(11), 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7110429

- Lv, W., Zhou, L., Wu, J., Cheng, J., Duan, Y., & Qian, W. (2025). Anti-HSV-1 agents: An update. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 15, 1471019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2024.1471019

- Madavaraju K, Koganti R, Volety I, et al. Herpes simplex virus cell entry mechanisms: an update. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:617578. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.617578

- Petti, S., & Lodi, G. (2019). The controversial natural history of oral herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. Oral Diseases, 25(8), 1850–1863. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13151

- Protto, V., Marcocci, M. E., Miteva, M., Piacentini, R., Li Puma, D. D., Grassi, C., Palamara, A. T., & De Chiara, G. (2022). Role of HSV-1 in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis: A challenge for novel preventive/therapeutic strategies. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 63, 102200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2022.102200

- Rechenchoski, D. Z., Faccin-Galhardi, L. C., Linhares, R. E. C., & Nozawa, C. (2017). Herpesvirus: An underestimated virus. Folia Microbiologica, 62(2), 151–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12223-016-0482-7

- Saleh, D., & Sharma, S. (2019). Herpes simplex type 1. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. (No DOI; online clinical reference).

- Shohael, A. M., Chowdhury, M. A., Riana, S. H., Ullah, M., Araf, Y., & Sarkar, B. (2021). An updated overview of herpes simplex virus-1 infection: Insights from origin to mitigation measures. Electronic Journal of General Medicine, 18(4), em296. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejgm/10870

- Su, D., Han, L., Shi, C., Li, Y., Qian, S., Feng, Z., & Yu, L. (2024). An updated review of HSV‑1 infection-associated diseases and treatment, vaccine development, and vector therapy application. Virulence, 15(1), 2389482. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2024.2389482

- Szczubiałka, K., Pyrć, K., & Nowakowska, M. (2016). In search for effective and definitive treatment of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infections. RSC Advances, 6(14), 11412–11421. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA26211B

- Tognarelli, E. I., Palomino, T. F., Corrales, N., Bueno, S. M., Kalergis, A. M., & González, P. A. (2019). Herpes simplex virus evasion of early host antiviral responses. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 9, 127. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2019.00127

- Zhang, J., Liu, H.-H., & Wei, B. (2017). Immune response of T cells during herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV‑1) infection. Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE B, 18(4), 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B1600436

- Zhu, H., & Zheng, C. (2020). The race between host antiviral innate immunity and the immune evasion strategies of herpes simplex virus 1. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 84(3), e00099-19. https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.00099-19

- Zhu, S., & Viejo-Borbolla, A. (2021). Pathogenesis and virulence of herpes simplex virus. Virulence, 12(1), 2670–2702. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2021.1964453