Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) is a neurotropic alpha herpesvirus and the leading viral cause of recurrent genital ulcer disease worldwide. Infection is lifelong, with alternating periods of lytic replication in the genital mucosa and latency in the sacral dorsal root ganglia and is a major cofactor for HIV acquisition and transmission.

- Enveloped, double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) virus with ~155 kb genome.

- Establishes latency in sensory neurons with frequent, often subclinical, reactivations.

- Causes significant psychosocial morbidity and serious complications in neonates and the immunocompromised.

Taxonomy and Classification of Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2)

Family: Herpesviridae

Subfamily: Alphaherpesvirinae

Genus: Simplexvirus

Species: Human alphaherpesvirus 2 (HSV-2).

Key taxonomic features:

- Short replication cycle, broad cell tropism, and lifelong latency in sensory ganglia are characteristic of alphaherpesviruses.

- HSV-1 and HSV-2 share ~83% amino acid identity in coding regions, but differ in antigenicity and tissue tropism (HSV-2 is strongly genital).

Structure and Morphology of Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2)

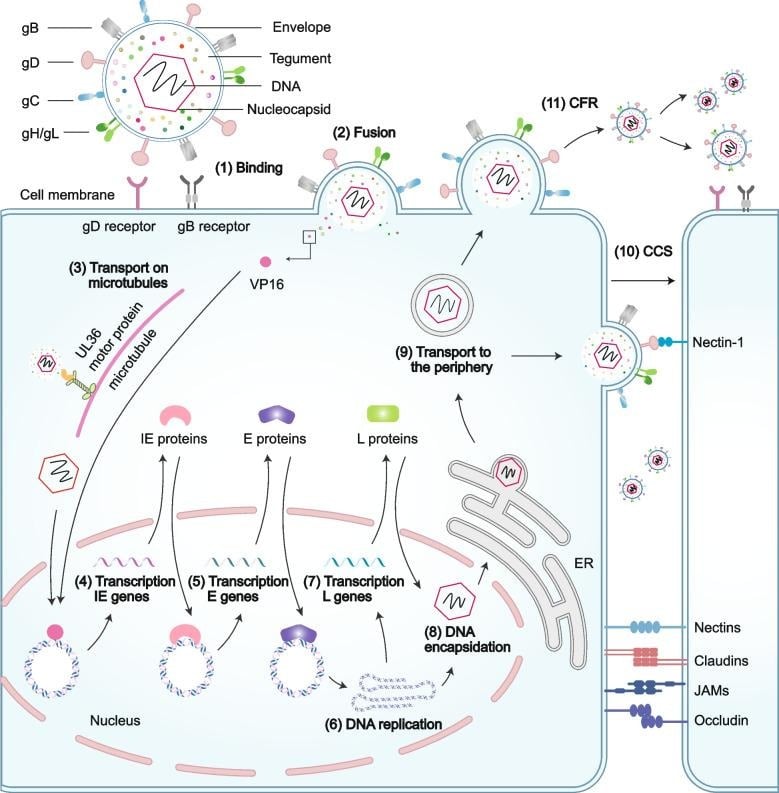

HSV-2 virions share the typical herpesvirus architecture.

- Basic virion layout:

- Core: linear dsDNA genome.

- Icosahedral capsid (~125 nm).

- Tegument: amorphous protein layer surrounding capsid.

- Envelope: host-derived lipid bilayer with ≥12 glycoproteins.

- Envelope glycoproteins (gB, gC, gD, gE, gG, gH, gI, gJ, gK, gL, gM, gN):

- Mediate attachment, fusion, cell-to-cell spread, and immune evasion.

- gB and gC bind heparan sulfate; gD engages entry receptors (nectin-1, HVEM).

- Capsid and tegument:

- Capsid: 162 capsomeres with six surface proteins.

- Tegument: ~22 viral proteins; includes transcriptional activators, host-shutoff factors, and motors for axonal transport.

Genome Organization and Proteins of Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2)

Genomic Organization

- Genome Composition: The HSV-2 genome consists of a large, linear double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) molecule approximately 152 kilobase pairs (kb) in length.

- Structural Architecture: The genome is organized into two unique segments: the Unique Long (UL) region and the Unique Short (US) region.

- Repeat Sequences: These unique regions are flanked by inverted repeat sequences, arranged in a specific modular structure described as $ab-UL-b’a’c’-US-ca$.

- Coding Capacity: The genome is estimated to encode at least 74 distinct genes, which produce a wide array of structural, regulatory, and enzymatic proteins.

- Origins of DNA Replication (Ori): HSV-2 contains three distinct replication origins that serve as binding sites for the initiation machinery.

- OriL: A single origin located within the UL region, characterized by a 144-bp perfect palindrome containing four recognition sites for the origin-binding protein.

- OriS: Present in two copies within the repeated ‘c’ regions flanking the US segment; it consists of a 45-bp imperfect palindrome with an A/T-rich spacer region.

- Regulatory Elements: The origins reside in strategic locations within the promoter-regulatory areas of divergently transcribed genes, like those encoding replication proteins, such as ICP8 and Pol, or immediately early proteins like ICP4.

- MicroRNAs: Recent studies showed that both OriL and OriS regions contained microRNAs, which might be involved in the regulation of viral pathogenicity or the transition from the lytic pathway to the latent one.

The complex genome of the HSV-2 virus facilitates efficient rolling circle replication or else the recombination-dependent mechanism for the formation of longer DNA concatemers. Their high significance is for the purpose of encapsidating the genome into the newly produced virions. Structural flexibility of the virus allows for high levels of recombination occurring during the infection.

Essential Replication Proteins

Seven essential viral proteins are encoded by the HSV-2 genome, which make up the basic machinery essential for viral DNA synthesis.

- UL9 (Origin-Binding Protein – OBP): A 94 kDa protein that is a dimer that specifically binds to GTTCGCAC sites in the origin region, with helicase/ATPase activity to distort the spacer region during initiation.

- ICP8 (UL29 – Major ssDNA-Binding Protein): A 130-kDa zinc metalloprotein that binds single-stranded DNA non-sequence-specific and cooperatively, and is essential for DNA replication, recombination, and the formation of nuclear replication compartments.

- UL30/UL42 (DNA Polymerase Complex):

- UL30: The catalytic subunit, providing 3’–5′ exonuclease and DNA polymerase activities.

- UL42: A processivity factor that acts like a “sliding clamp,” allowing it to bind the catalytic subunit to the DNA; interestingly, instead of sliding along the DNA strand, its “hops” along the strand.

- UL5/UL8/UL52 (Helicase/Primase Complex): A heterotrimer complex which includes the UL5/UL52 subcomplex as the ATPase, helicase, and primase, and UL8 as the coordinator of the process.

Auxiliary and Structural Proteins

Beyond the core replication machinery, HSV-2 produces numerous auxiliary enzymes and structural proteins that facilitate environmental stability and host cell entry.

- Auxiliary Enzymes:

- UL23 (Thymidine Kinase – TK): Phosphorylates thymidine and nucleoside analogs (like acyclovir); it is essential for replication in non-dividing cells such as neurons.

- UL39/UL40 (Ribonucleotide Reductase – RR): A two-subunit complex (RR1/RR2) that generates deoxyribonucleotides; RR1 (ICP6) also functions as a chaperone and inhibits host cell apoptosis.

- UL12 (Alkaline Nuclease): A 5’–3′ exonuclease involved in processing DNA concatemers and promoting single-strand annealing (SSA) recombination.

- Capsid and Tegument Proteins:

- VP5 (UL19): The major protein constituting the icosa-pentahedral capsid, which is composed of 162 capsomeres.

- VP16 (UL48): A potent trans activator delivered to the host nucleus upon entry to initiate the expression of immediate-early genes.

- VP22 (UL49): A major tegument protein involved in various stages of the viral life cycle.

- Envelope Glycoproteins: The lipid envelope is embedded with at least 12 glycoproteins (gB, gC, gD, gE, gG, gH, gI, gJ, gK, gL, gM, and gN).

- gD (UL27): The primary receptor-binding protein; it contains a Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) and a Pro-fusion Domain (PFD) that triggers the core fusion machinery.

- gB (UL26): A Class III fusogen that undergoes significant conformational changes from a globular pre-fusion form to a trimeric spike-like post-fusion form to merge the viral and host membranes.

- gH/gL Heterodimer: Acts as a fusion regulator; gH interacts with host integrins (e.g., $\alpha v\beta 3$) to facilitate calcium signaling and capsid transport to the nuclear pore.

- gG-2: A type-specific glycoprotein used in diagnostic serology to differentiate HSV-2 from HSV-1.

- gE/gI Heterodimer: Specifically mediates cell-to-cell spread by accumulating at tight junctions and facilitating the movement of virions to adjacent uninfected cells.

Replication Cycle of Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2)

Fig 1: Structure, Morphology, and Host cell entry and transmission of HSV (Bai et al., 2024)

- Attachment and entry:

- gB/gC bind heparan sulfate; gD then engages nectin-1 or HVEM.

- Conformational relay activates gH/gL and gB to drive membrane fusion.

- Capsid–tegument complex released and traffics to nucleus via microtubules.

- Nuclear events and gene expression:

- Genome circularizes; immediate-early genes expressed using tegument VP16.

- Sequential expression: α → β → γ, tightly controlled by ICP4, ICP0, ICP27, ICP22.

- DNA replication:

- Bidirectional theta replication from origins, then rolling-circle replication producing concatemers.

- Seven essential replication proteins (UL9, UL29, UL30, UL42, UL5/UL8/UL52) assemble at origins.

- Assembly and egress:

- Capsid assembly and DNA packaging in the nucleus; nuclear egress via primary envelopment/de-envelopment.

- Secondary envelopment at trans-Golgi/endomembrane compartments; virions released by exocytosis.

- Latency and reactivation:

- Latency in sacral dorsal root ganglia neurons; limited gene expression (LATs, some non-coding RNAs).

- Reactivation triggered by stress, immunosuppression, hormonal changes; minimal genetic change across episodes.

Pathogenesis and Host Immune Response of Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2)

- Clinical pathogenesis:

- Primary genital infection: epithelial lytic replication, local inflammation, neuronal invasion.

- Latent infection in sensory ganglia; recurrent mucocutaneous lesions or asymptomatic shedding.

- Severe outcomes: neonatal disseminated disease, meningitis, encephalitis, increased HIV susceptibility.

- Innate immune interactions:

- HSV 2 causes acute down-regulation of many immune genes in mucosal tissues, which makes it difficult to recognize it early. From the transcriptome analysis, it has been seen that it downregulates interferon-stimulated genes, as well as the cell cycle.

- The pattern recognition receptors, such as TLR2, TLR9, cGAS-STING, and RIG-I-like receptors, recognize the DNA/RNA intermediates of the virus (best seen in HSV 1, but through a shared pathway).

- Viral protein functions include blocking interferon production/signaling, apoptosis, and autophagy inhibition.

- Adaptive immunity:

- Robust HSV2-specific CD4 and CD8 T responses in tissue, including mucosa and ganglia; strength of response and localization correlate with control of reactivation.

- Broad antibody response to glycoproteins and to multiple infected cell proteins: capsid proteins and tegument proteins; may also induce broad anti-ICP and anti-replication protein response with live-attenuated vaccines.

Epidemiology and Transmission of Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2)

- Global burden:

- WHO estimates ~491–500 million people aged 15–49 infected with HSV-2 (2016 data).

- Seroprevalence varies by region, sex, and socioeconomic status; higher in women and in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Transmission:

- Predominantly sexual (vaginal, anal, oral) via contact with mucosa or abraded skin.

- Efficient transmission during symptomatic and asymptomatic shedding; 50–80% of reactivations are subclinical with brief shedding episodes.

- Vertical transmission: intrapartum exposure leads to neonatal infection, especially with primary maternal infection near delivery.

- Association with HIV:

- HSV-2 approximately triples the risk of HIV acquisition; inflammation and mucosal disruption, plus recruitment of HIV-susceptible cells, contribute.

Clinical Manifestations of Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2)

Genital / Mucocutaneous Disease (Most Common)

- Primary genital herpes (first episode, often most severe)

- Painful grouped vesicles → pustules → ulcers on vulva, vagina, cervix, penis, perineum, perianal skin.

- Prominent local pain/itching (≈98%), dysuria (≈63%), and tender inguinal lymphadenopathy (≈80%) in the first-episode of disease.

- Frequent systemic symptoms: fever, malaise, myalgia, headache in ≈67% of primary episodes.

- Women tend to have more severe symptoms and longer lesion duration than men; the mean is 19 days to complete healing in primary episodes.

- Recurrent genital herpes

- Typically milder, unilateral, fewer lesions, shorter duration (mean ≈10 days), and rare systemic symptoms.

- Up to 25% of recurrences are asymptomatic; patients may only notice minimal tingling, burning, or small fissures.

- Prodromal sensory symptoms: burning, tingling, or pain in the genital/buttock/thigh area preceding lesions by hours–1–2 days.

- Extragenital recurrences on buttocks, thighs, or perianal skin (~20% have extragenital lesions).

- Symptom spectrum & patient-reported experience (recent data)

- Commonly reported symptoms: itching (100%), sores/lesions/blisters (97%), pain (93%), tingling (80%), burning (70%), plus tiredness and flu-like symptoms during outbreaks.

- Patients highlight sores/lesions/blisters as the most bothersome symptom, associated with activity limitation and sexual avoidance.

- Oral and other mucosal lesions

- HSV-2 can cause orolabial or oral mucosal ulcers (less frequent than HSV-1) and herpetic whitelow, especially in individuals with genital–oral or occupational exposure.

Complicated and Systemic Manifestations of Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2)

- Neurological complications (aseptic meningitis/meningitis-radiculitis)

- HSV-2 is one of the most common causes of viral meningitis in adults and the leading cause of recurrent meningitis (Mollaret’s).

- Typical meningitis presentation: headache (100%), nausea/vomiting (~83%), meningismus (~57%), fever (~55%), often in young adults (mean age ≈32.5 years; predominance in females).

- Many have a history of genital herpes or concurrent genital lesions, but meningitis can occur without obvious mucocutaneous disease.

- Recurrent episodes of aseptic meningitis with symptom-free intervals are characteristic; prognosis usually favorable with full recovery.

- HSV-2 encephalitis and cerebrovascular events

- Less common than HSV-1 encephalitis, but can cause encephalitis with confusion, behavioral changes, focal deficits, and seizures.

- Systematic review of HSV-related cerebrovascular disease:

- HSV-2 is more often linked to ischemic stroke via multifocal large-vessel vasculitis, often in association with meningitis/encephalitis.

- Presentations include acute hemiparesis or stroke-like symptoms; outcome generally more favorable than HSV-1 hemorrhagic complications.

- Case reports describe cranial neuropathies (e.g., abducens nerve palsy) accompanying HSV-2 meningoencephalitis, with headache, altered behavior, and diplopia.

- Radiculomyelitis and sacral autonomic dysfunction

- Sacral radiculitis/radiculomyelitis may cause severe lumbosacral pain, urinary retention, constipation, or fecal incontinence, often in women or men with proctitis.

- In a classic cohort of primary genital herpes, sacral autonomic dysfunction occurred in ≈2% of first-episode patients.

- Neonatal HSV-2 disease

- Three major forms:

- Skin–eye–mouth (SEM): localized vesicular lesions; relatively better prognosis.

- Central nervous system disease: seizures, lethargy, poor feeding; high risk of long-term neurologic sequelae.

- Disseminated disease: multi-organ failure, coagulopathy, high early mortality (≈12–25% in recent series) despite therapy.

- Many neonates present with fever, lethargy, poor feeding, seizures, or rash; maternal genital lesions may be absent or undocumented.

- Three major forms:

- Other systemic / organ-specific manifestations

- HSV-2 meningitis/encephalitis with visceral involvement (e.g., hepatitis, pneumonitis), particularly in pregnancy or immunosuppression, is often severe and potentially fatal.

- Ocular disease: keratitis, blepharitis, conjunctivitis, and rarely necrotizing retinitis, sometimes during reactivation.

- In immunocompromised hosts, chronic, extensive, or hypertrophic mucocutaneous ulcers and disseminated visceral disease are more frequent and prolonged.

- Asymptomatic infection and subclinical shedding (key for transmission)

- A significant number of people infected with HSV-2 appear clinically asymptomatic, though they frequently show subclinical genital shedding.

- Such shedding bouts tend to be acute, lasting from hours to 1 day, and frequent, occurring across the genital tract, even in individuals with no lesions.

- Impact on quality of life (QoL) and psychosocial manifestations

- Beyond physical symptoms, recurrent HSV-2 genital herpes is strongly associated with:

- Anxiety, worry, and fear of recurrences and transmission.

- Concerns about disclosure, relationship strain, and loss of self-esteem/confidence.

- Qualitative studies show these psychosocial burdens can be persistent even in patients with infrequent physical recurrences.

- Beyond physical symptoms, recurrent HSV-2 genital herpes is strongly associated with:

Laboratory Diagnosis of Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2)

Direct detection (preferred):

- NAATs (PCR) from genital lesions or mucosal swabs: high sensitivity and type-specific; recommended to distinguish HSV-1 vs HSV-2 due to different recurrence patterns and counseling implications.

- Virus culture is less sensitive, slower; useful for phenotypic drug-resistance testing.

Serology:

- Type-specific IgG (gG-based) detects prior infection; not useful for acute lesion diagnosis, but important for epidemiology and counseling.

Genotyping and resistance testing:

- Sequencing of TK (UL23) and DNA polymerase (UL30) identifies mutations conferring acyclovir (ACV) resistance.

Treatment and Antiviral Therapy of Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2)

First-line drugs:

- Nucleoside analogues: acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir, inhibit viral DNA polymerase following phosphorylation by viral TK.

- Used as:

- Episodic therapy for outbreaks.

- Suppressive therapy to reduce recurrences and shedding.

Drug resistance:

- Mainly in immunocompromised hosts with prolonged therapy; TK and, less commonly, DNA polymerase mutations (including in HSV-2) confer ACV resistance.

- Second-line agents: foscarnet, cidofovir for ACV-resistant HSV; toxicities limit long-term use.

Emerging therapies:

- Novel direct-acting antivirals (e.g., helicase/primase inhibitors), small molecules against glycoproteins/host fatty acid synthase, interference with the virion envelope and replication (e.g., UCM05 for HSV-2).

- The natural compounds that interfere with cell attachment, entry, replication, and latency/reactivation include flavonoids that exhibit in vitro anti-HSV activity.

- Intensive development of vaccines such as multiepitope mRNA vaccines targeting gB, ICP0, ribonucleotide reductase, and VP23, and live attenuated HSV 2 vaccines targeting broad responses to infected cell proteins.

Prevention and Control of Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2)

Individual-level measures:

- Consistent condom use reduces but does not eliminate transmission risk.

- Daily suppressive antiviral therapy lowers recurrence frequency and asymptomatic shedding, thereby reducing transmission.

- Counseling on disclosure, symptom recognition, and sexual practices.

Public health strategies:

- Screening high-risk populations with type-specific serology may be considered, but universal screening is not recommended due to limited impact on outcomes and psychosocial harms.

- Prevention of neonatal herpes: management of pregnant women with known HSV-2, including suppressive ACV near term and cesarean delivery if active lesions or prodrome at labor.

Vaccines and prospects:

- No licensed HSV-2 vaccine; subunit gD vaccines have failed to provide durable, broad protection.

- Next-generation approaches (multiepitope mRNA, live-attenuated, vectored vaccines) aim to induce robust mucosal T-cell immunity and broad antibody responses against multiple structural and non-structural proteins.

Conclusion

HSV-2 is a highly prevalent sexually transmitted alphaherpesvirus with a complex dsDNA genome, sophisticated immune-evasion strategies, and a lifelong latent–lytic cycle centered on genital mucosa and sacral ganglia. Despite effective nucleoside analogue therapy, there is no cure, and recurrences with asymptomatic shedding sustain a large global burden and synergize with HIV. Advances in genomics, immunology, and antiviral pharmacology are clarifying HSV-2 biology and host interactions, informing the development of new antivirals and vaccines that target diverse viral proteins and host pathways. Continued integration of molecular insights with clinical and public health interventions will be crucial to reduce the morbidity, transmission, and complications associated with HSV-2 infection.

References

- Abrão, E. P., Burrel, S., Désiré, N., Bonnafous, P., Godet, A., Caumes, E., Agut, H., & Boutolleau, D. (2015). Impact of HIV-1 infection on herpes simplex virus type 2 genetic variability among co-infected individuals. Journal of Medical Virology, 87(3), 451–458. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24057

- Bai, L., Xu, J., Zeng, L., Zhang, L., & Zhou, F. (2024). A review of HSV pathogenesis, vaccine development, and advanced applications. Molecular Biomedicine, 5(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43556-024-00199-7

- Banerjee, A., Kulkarni, S., & Mukherjee, A. (2020). Herpes simplex virus: The hostile guest that takes over your home. Frontiers in Microbiology, 11, 733. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00733

- Chang, W., Jiao, X., Sui, H., Goswami, S., Sherman, B. T., Fromont, C., Caravaca, J. M., Tran, B., & Imamichi, T. (2022). Complete genome sequence of herpes simplex virus 2 strain G. Viruses, 14(3), 536. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14030536

- Geltz, J. J., Gershburg, E., & Halford, W. P. (2015). Herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) infected cell proteins are among the most dominant antigens of a live-attenuated HSV-2 vaccine. PLOS ONE, 10(2), e0116091. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0116091

- Jaishankar, D., & Shukla, D. (2016). Genital herpes: Insights into sexually transmitted infectious disease. Microbial Cell, 3(9), 438–450. https://doi.org/10.15698/mic2016.09.523

- López-Muñoz, A. D., Rastrojo, A., Kropp, K. A., Viejo-Borbolla, A., & Alcamí, A. (2021). Combination of long- and short-read sequencing fully resolves complex repeats of herpes simplex virus 2 strain MS complete genome. Microbial Genomics, 7(6), 000579. https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.000579

- Majewska, A., & Młynarczyk-Bonikowska, B. (2022). 40 years after the registration of acyclovir: Do we need new anti-herpetic drugs? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(7), 3627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23073627

- Minaya, M. A., Jensen, T. L., Goll, J. B., Korom, M., Datla, S. H., Belshe, R. B., & Morrison, L. A. (2017). Molecular evolution of herpes simplex virus 2 complete genomes: Comparison between primary and recurrent infections. Journal of Virology, 91(21), e00942-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00942-17

- Piperi, E., Papadopoulou, E., Georgaki, M., Dovrat, S. B., Bar Illan, M., Nikitakis, N. G., & Yarom, N. (2023). Management of oral herpes simplex virus infections: The problem of resistance. A narrative review. Oral Diseases. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.14904

- Pillay, R., Naidoo, P., & Mkhize-Kwitshana, Z. (2025). Exploring gene expression changes in murine female genital tract tissues following single and co-infection with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis and herpes simplex virus type 2. Pathogens, 14(8), 642. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14080642

- Šudomová, M., & Hassan, S. T. S. (2023). Flavonoids with anti-herpes simplex virus properties: Deciphering their mechanisms in disrupting the viral life cycle. Viruses, 15(12), 2459. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15122459

- Suneesh, N. S., Dhotre, K. P., Mahajan, P., Dass, D., Banerjee, A., Siddiqi, N. J., Malik, A., Joshi, M., Khan, A. A., Nema, V., Mukherjee, A., Araújo-Pereira, M., & Bhattacharya, A. (2025). Reverse vaccinology-based design of multivalent multiepitope mRNA vaccines targeting key viral proteins of herpes simplex virus type-2. Frontiers in Immunology, 16, 1469440. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1469440

- Verzosa, A. L., McGeever, L. A., Bhark, S.-J., Delgado, T., Salazar, N., & Sanchez, E. L. (2021). Herpes simplex virus 1 infection of neuronal and non-neuronal cells elicits specific innate immune responses and immune evasion mechanisms. Frontiers in Immunology, 12, 644664. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.644664

- Zhu, S., & Viejo-Borbolla, A. (2021). Pathogenesis and virulence of herpes simplex virus. Virulence, 12(1), 2670–2702. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2021.1988678