Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive, facultative, non-spore-forming, intracellular rod bacteria. They are responsible for causing the infection listeriosis. Listeria causes severe infections in immunocompromised, the elderly, infants and pregnant women with only a self-limited gastrointestinal infection in the immunocompetent. monocytogenes are catalase positive bacteria and show beta-hemolytic activity when grown on blood agar. It was revealed to be a foodborne illness linked to a variety of foods. While L. monocytogenes is not the most common foodborne illness, it has the highest mortality rate secondary to its unique virulence factors.

Taxonomic Classification Level

Kingdom: Bacteria

Phylum: Bacillota

Class: Bacilli

Order: Caryophanales

Family: Listeriaceae

Genus: Listeria

Species: Listeria monocytogenes

The Listeria family consists of 10 different species with L. monocytogenes found most consistently in humans. L. monocytogenes has 13 different stereotypes based on a variety of flagellar and surface antigens. However, there are only three serotypes (1/2a, 1/2b/ 4a) that inflict disease in humans.

Morphology and Microscopy

Morphology

L. monocytogenes are gram positive short rod-shaped bacteria. They tend to appear as cocco-bacillary in clinical materials. Typically, they measure to about 0.4 – 0.5 µm wide and 0.5 – 2.0 µm long when observed under the microscope. They may occur singly, in pairs or in short chains. Longer filaments can sometimes be observed under stress or variant forms as well. L. monocytogenes is catalase-positive and oxidase negative and exhibits beta-hemolytic activity on blood agar, which can assist in identification.

L. monocytogenes displays motility at lower temperatures (around 20–30 °C) through peritrichous flagella which produces a characteristic “tumbling” motility in wet mounts or hanging drop preparations. At body temperatures (≈37 °C), the bacterium does not express flagella, and therefore appears non-motile by conventional motility tests at this temperature.

Microscopy

Gram staining has been the cornerstone microscopic technique to establish L. monocytogenes as a small gram-positive rod. It appears as short rods of coccoid forms, especially in direct clinical specimens, which may sometimes be misinterpreted as other gram-positive organisms in morphology are not carefully assessed. L. monocytogenes is a facultative intracellular bacterium. Fluorescence microscopy and confocal microscopy are often used in research to observe actin-based motility inside host cells (actin “comet tails”).

In Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) studies, l. monocytogenes cells present typical gram-positive architecture with thick cell walls and internal cytoplasmic structures. In Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) has been used in research to visualize bacterial aggregates and biofilm formation on surfaces.

Cultural and Growth Characteristics

Listeria monocytogenes is a facultative anaerobic, psychrotrophic foodborne pathogen able to grow under a wide range of environmental conditions which contributes to its persistence in food and clinical settings. It is typically cultured in nutrient rich media such as Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) or Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB), Listeria Selective Agars (LPM, Oxford, PALCAM), which supply essential amino acids and growth factors required due to the organism’s auxotrophic requirements.

In laboratory practices, colonies appear on BHI agar after around 24 hours at 37 °C, and enrichment broths such as TSB with yeast extract are effective for isolation and enumeration.

L. monocytogenes exhibits psychrotrophic growth growing from near 0 °C up to ~45 °C, with optimal rates between 30 – 37 °C, allowing proliferation even under refrigeration. Growth at refrigeration temperatures (<4 °C) is slow, but possible, contributing to its importance in chilled food samples. L. monocytogenes is salt tolerant. It can grow in moderate salt concentrations (e.g., ~10 % NaCl). However, with higher salt concentration and limiting pH, their growth is generally reduced. It is capable of growth across pH values ranging from roughly ~4.4 to ~9.6 depending on temperature and medium while maintaining its most active growth in the near-neutral range (pH 6-8). Growth at very low pH is limited and may require extended incubation times.

While L. monocytogenes grows in aerobic conditions, growth can be improved in CO₂ enriched atmospheres. High CO₂ tends to be inhibitory.

Epidemiology

According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), approximately 1,600 people get listeriosis each year with approximately 260 people dying from the disease. The disease is most prevalent in pregnant women, infants, immunocompromised and elderly people.

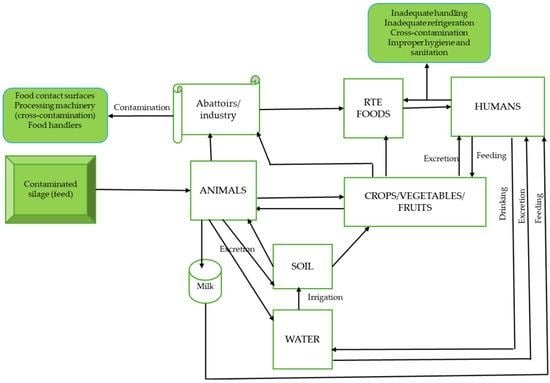

L. monocytogenes in ubiquitous environmental saprophytes, with a widespread distribution, occurring in varied environmental niches including soil, water and decaying vegetation. These bacteria can also be found in the human digestive tract. Foods with highest rates of L. monocytogenes related infections include ready-to-eat foods and others like:

- Raw sprouts

- Unpasteurized milk

- Cold deli meats

- Soft cheeses

- Cold hot dogs

- Smoked seafood

These can generally be isolated from fresh saltwater, sewage, soil, sludge, decaying vegetation, grazing areas, stale water supplies and poorly prepared animal feeds. Dairy products, fruits, vegetables, cattle, sheep and fowls are other sources from which these bacteria can be isolated.

There are several sources and routes via which transmission of or contamination with L. monocytogenes can occur. The channels include food and food-processing facilities, humans, animals and environmental sources (water and soil). L. monocytogenes recovered from either food or humans or animals has the potential of being transmitted through the said medium to their counterparts.

Pathogenesis and Virulence

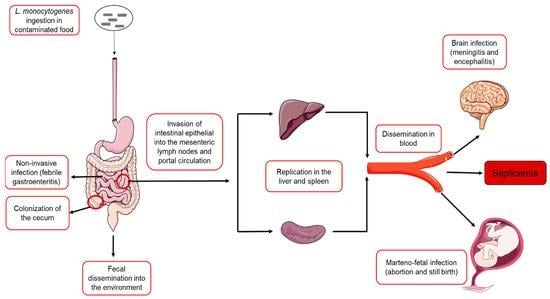

L. monocytogenes is a known etiological agent of food-borne gastrointestinal disease- Listeriosis, meningitis, pregnancy associated infections (neonatal sepsis, meningitis, rarely granulomatosis infantiseptica).

Pathogenesis

The consumption of contaminated food is believed to be the principal route of infection, although infections can occur via contact with animals and neonatal spread as well. The bacterium survives gastric acid and bile to invade the intestinal epithelium, mediated by surface proteins called internalis (InA/InB) that bind host receptors and trigger the uptake into phagocytic cells.

Once internalized, L. monocytogenes escapes the phagolysosome using listeriolysin O (LLO) and phospholipases. They then replicate within the cell cytoplasm and exploit the host cytoskeleton by expressing ActA, which drives actin polymerization to propel the bacterium through the cytoplasm and into the adjacent cells facilitating systemic spread. Once the bacteria is phagocytosed, it never becomes extracellular again. This intracellularly spreading character of L. monocytogenes allows the pathogen to cross critical host barriers including the intestinal barrier, blood-brain barrier and placenta leading to severe invasive diseases.

Virulence

Virulence of L. monocytogenes is primarily mediated by a well-characterized cluster of genes located within Listeria Pathogenicity Island-1 (LIPI-1). This region encodes several virulence determinants including prfA, hly, plcA, plcB, actA and mpl which are coordinated by transcriptional activator PrfA, the master regulator or virulence gene expression.

A key virulence factor is listeriolysin-O (LLO), encoded by hly (pore forming cytotoxin) that enables escaping of phagosomes into host cytoplasm. Two phospholipases- PlcA (phosphatidylinositol-specific) and PlcB (broad range phospholipase C) further facilitate membrane disruption and intracellular survival.

ActA promotes actin polymerization, enabling intracellular motility and direct cell-to-cell spread, thereby avoiding extracellular immune defenses.

Cell invasion is mediated by internalis (InlA, InlB) which bind host receptors such as E-cadherin and Met, promoting bacterial uptake into non-phagocytic cells.

Clinical Manifestations

Disease caused: Listeriosis

Listeriosis is a group of disorders caused by L. monocytogenes and is clinically defined when an organism is isolated from blood, CSF or otherwise normally sterile sites.

- GI Listeriosis

- It is generally presented as asymptomatic or mild, self-limiting illness.

- When symptomatic, affected individuals may experience gastrointestinal upset accompanied by systemic features such as muscle aches, headache and fever.

- Incubation period: notably variable; ranging from approximately 2 to 67 days, depending on host susceptibility and clinical form of disease.

- Invasive Listeriosis

- It is typically initiated by bacteremia and sepsis with subsequent hematogenous dissemination to secondary sites including CNS

- CNS involvement most commonly manifests as meningitis which is often subacute and indolent in onset presenting with fever, headache and nuchal rigidity.

- In severe cases, encephalitis may develop, leading to prominent neurological symptoms such as seizures and altered mental status.

- Pregnancy-associated and Neonatal Listeriosis

- Maternal infection most frequently occurs during the third trimester and is often characterized by mild, influenza-like symptoms.

- L. monocytogenes can cross the transplacental barrier and cause intrauterine fetal death, spontaneous abortion, and preterm labor.

- Neonatal infection is often severe and may present with febrile gastroenteritis, acute sepsis, pneumonia, meningitis or granulomatosis infantiseptica characterized by nodular skin rash.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Specimens: blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), amniotic/placental fluid)

Direct gram staining of CSF or blood may occasionally show small gram-positive rods but sensitivity is low due to often low bacterial loads in these specimens. Hence, culture remains the gold standard for diagnosis.

Culture

L. monocytogenes grows on common bacteriological media such as blood agar and brain hear infusion agar with small, grey colonies often exhibiting β-hemolysis after 24-48 hours incubation at 37 °C. non-sterile specimens typically require selective enrichment and plating to recover organisms from mixed flora.

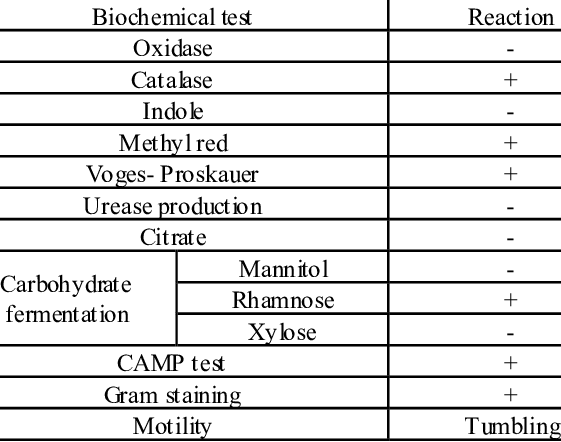

Biochemical and Identification Tests of Listeria monocytogenes

Listeria monocytogenes is identified using a combination of microscopic characteristics and biochemical reactions. It appears as a gram positive, short rod-shaped bacterium and is catalase positive organism which helps it differentiate from other gram-positive organisms. The organism ferments carbohydrates without gas production.

Motility testing is an important diagnostic feature for L. monocytogenes. It demonstrates tumbling motility at 20–25 °C and produces an umbrella-shaped growth pattern in semi-solid motility media. However, motility is usually absent at 37°C.

Hemolysis testing is another widely used test for species differentiation. On blood agar, L. monocytogenes produces a narrow zone of β-hemolysis caused by listeriolysin-O.

Further biochemical differentiation relies on metabolic tests. L. monocytogenes typically shows positive Voges-Proskauer and methyl red reactions, hydrolyzes esculin and ferments rhamnose but not xylose or mannitol. These combined biochemical characteristics are used in conventional laboratory identification and confirmation of the pathogen.

Biochemical and phenotypic tests, including motility at 25 °C, catalase positivity and hemolysis on blood agar, helps confirm presumptive isolates as L. monocytogenes

Source: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Biochemical-characterization-of-L-monocytogenes_tbl3_236154530

Molecular methods

PCR targeting genes like hly provides rapid and sensitive detection from clinical material or after enrichment. Real-time PCR has high specificity and can detect L. monocytogenes even when cultures are negative due to prior antibiotic treatment.

Serological tests

Serological tests like anti-listeriolysin O titers have been described but are not routinely recommended due to limited diagnostic utility.

Treatment

The primary treatment for invasive listeriosis is antibiotic therapy, tailored to disease severity and host risk factors. L. monocytogenes is almost uniformly susceptible to beta-lactam antibiotics and the first line therapy for serious infections such as bacteremia, meningitis or maternal-neonatal disease, is intravenous (IV) Ampicillin or Amoxicillin. These are frequently combined with an aminoglycoside (like Gentamycin) to exploit synergistic bactericidal activity. In adults with meningitis, Ampicillin is administered at high doses often for at least 2-3 weeks.

For patients with Penicillin allergy, trimethoprim-sulfomethoxazole (TMP-SMX) is an effective alternative. Other alternatives include Meropenem and Linezolid.

In mild noninvasive cases of gastrointestinal listeriosis in immunocompetent individuals, antibiotic therapy is often not required as symptoms tend to be self-limiting. Treatments are reserved for high-risk groups.

Duration of therapy should be individualized based on clinical response and site of infection, with longer courses for CNS involvement, endocarditis or other deep-seated infection.

Prevention and Control

Prevention of Listeria monocytogenes infection relies on food hygiene, proper processing and safe handling. In the food industry, Good Hygienic Practices (GMP) and HACCP-based systems help prevent contamination. Regular environmental monitoring is critical, especially in wet, cool areas where Listeria can persist. Pasteurization of dairy products and thorough cooking of animal foods effectively inactivate the bacterium.

For consumers, especially the high-risk groups, preventive measures include avoiding unpasteurized dairy, thoroughly cooking meats, refrigerating foods below 4 °C and preventing cross-contamination in the kitchen. Combined industry controls and consumer precautions reduce the incidence of listeriosis.

References

ACIR. (n.d.). Listeria monocytogenes. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. https://acir.aphis.usda.gov/s/cird-taxon/a0u3d000000BEUPAA4/listeria-monocytogenes

Bierne, H., Kortebi, M., & Descoeudres, N. (2021). Microscopy of intracellular Listeria monocytogenesin epithelial cells. In Methods in Molecular Biology (Vol. 2220). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32975777/

Bolívar, A., & Pérez Rodríguez, F. (2023). Listeria in food: Prevalence and control. Foods, 12(7), 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12071378

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, August 12). Caring for patients with listeriosis. https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/hcp/clinical%20care/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Preventing Listeria infection. https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/prevention/index.html

Cole, M. B., Jones, M. V., & Holyoak, C. (1990). The effect of pH, salt concentration and temperature on the survival and growth of Listeria monocytogenes. Journal of Applied Bacteriology, 69(1), 63–72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2118897/

Frontiers in Microbiology. (2019). Jamshidi, A. Significance and characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes [Review]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6500651/

Janda, J. M., & Young, S. A. (2001). Listeria monocytogenes and listeriosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 14(3), 584–640. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.14.3.584-640.2001

Liu, D., Lawrence, M. L., Austin, F. W., & Ainsworth, A. J. (2015). Isolation, identification, and characterization of Listeriaspp. from foods of animal origin. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4825267/

MDPI. (2023). Listeria monocytogenes. Foods, 14(7), 1266. https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/14/7/1266

NCBI Bookshelf. (n.d.). Listeria monocytogenes. In Listeria: Microbiology, epidemiology, prevention, detection, and treatment. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534838/

Oklahoma State University Extension. (n.d.). Food pathogens of concern: Listeria monocytogenes. https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/food-pathogens-of-concern-listeria-monocytogenes.html

Peel, M., Donachie, W., & Shaw, A. (1988). Temperature-dependent expression of flagella of Listeria monocytogenesstudied by electron microscopy. Journal of General Microbiology, 134(8), 2171–2178. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3150978/

Peterkin, P. I. (2008). Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC372831/

Procop, G. W., Church, D. L., Hall, G. S., Janda, W. M., Koneman, E. W., Schreckenberger, P. C., & Woods, G. L. (2016). Koneman’s color atlas and textbook of diagnostic microbiology (7th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Ramaswamy, V., Cresence, V. M., Rejitha, J. S., Lekshmi, M. U., Dharsana, K. S., Prasad, S. P., & Vijila, H. M. (2007). Listeria—Review of epidemiology and pathogenesis. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection, 40(4), 4–13. https://www.vetmed.auburn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Ramaswamy-et-al-JMII-40_4-2007.pdf

ResearchGate. (n.d.). Scanning electron microscopy images of Listeria monocytogenes aggregates on Acanthamoeba. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Scanning-electron-microscopy-images-of-Listeria-monocytogenes-aggregates-on-Acanthamoeba_fig1_260371537

Rowan, N. J., Anderson, J. G., & Candlish, A. A. G. (2000). Cellular morphology of rough forms of Listeria monocytogenesisolated from clinical and food samples. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 31(4), 319–322. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1472-765x.2000.00821.x

ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.-a). Listeria – Growth and environmental profile. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/listeria

ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.-b). Listeria monocytogenes – Growth and survival characteristics. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/food-science/listeria-monocytogenes

Stephan, R., Althaus, D., Kittl, S., Aymerich, M. T., Teuber, M., & Tasara, T. (2015). Bioprotective strategies to control Listeria monocytogenesin food products and processing environments. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(21), 10481. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110481

UK Health Security Agency. (2021). Identification of Listeria species and other non-sporing Gram-positive rods. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/smi-id-03-identification-of-listeria-species

UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations. (n.d.). Listeria monocytogenes. https://www.rcpath.org/static/…/UK-SMI-ID-03i42-Identification-of-Listeria-species.pdf

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Listeria monocytogenes. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Listeria_monocytogenes

PMC Articles. (n.d.-a). Characterisation of the growth behaviour of Listeria monocytogenes in Listeria synthetic media. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10667646/

PMC Articles. (n.d.-b). Listeria monocytogenes: Cultivation and laboratory maintenance. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3920655/