Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a well-known and well-utilized laboratory technique for the in-vitro enzymatic amplification of a nucleic acid, DNA (or RNA: following the reverse transcription of a single-stranded RNA to form complementary DNA or cDNA). PCR amplifies specific or target DNA sequences, also called DNA templates, from very tiny amounts into a large number. During PCR, a thermostable DNA polymerase, either natural or synthetic, is used to extend a primer and synthesize DNA. The general process of PCR involves multiple cycles of heat-based DNA denaturation, followed by binding of primers (annealing) and extension of the newly synthesized DNA strands.

The theoretical procedure for PCR was initially known to have been given by Keppe and his team in 1971. However, an American biochemist, Kary Mullis, is typically credited with describing the complete PCR procedure and demonstrating its experimental application in 1985. Mullis was later granted the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Following its invention, PCR has been highly applicable for diagnostics, research, and forensics purposes.

Principle of Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

The fundamental principles of PCR are based upon the ideas of nucleic acid hybridization and enzyme-mediated amplification. Nucleic acid hybridization is the ability of a single-stranded nucleic acid sequence to complementarily bind to other single-stranded sequences to form a double-stranded molecule. A highly heat-stable enzyme, DNA polymerase, synthesizes a new DNA strand based on the target DNA strand. DNA polymerases are the enzymes that use initiating mono-deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) to catalyze the synthesis of polydeoxyribonucleotides or a new DNA strand.

PCR includes multiple repeating cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension for nucleic acid amplification.

Denaturation: Heating of a double-stranded template DNA to break its hydrogen bonds between the nitrogenous base pairs and to convert it into two ss-DNA molecules

Annealing: Primers hybridization with denatured ss-DNA

Extension: Addition of nucleotides to the 3’ end of the primers for DNA synthesis

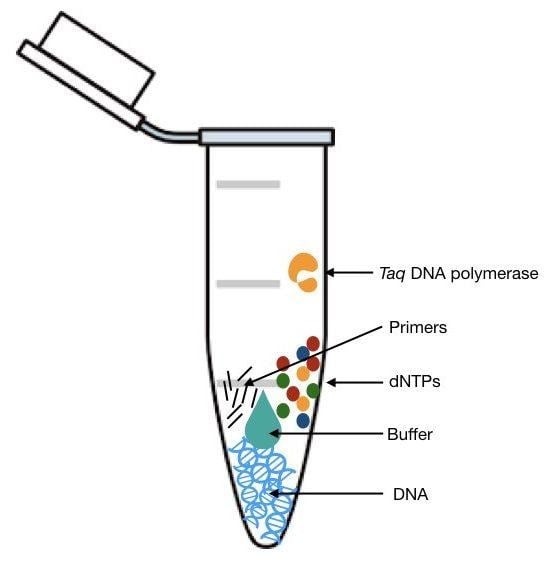

Key Components of the Master Mix / Components of PCR

A PCR contains the following components. Without an individual component, an amplification reaction cannot occur.

- Template DNA

- Primers (Forward and Reverse)

- DNA Polymerase

- Nucleotides (dNTPs or deoxynucleotide triphosphates)

- Sterile Water

- Additional Reagents / Buffers (Magnesium Salt, Potassium Salt, DMSO, Formamide, BSA, Betaine)

Source: https://geneticeducation.co.in/polymerase-chain-reaction-pcr/

Steps of the PCR Cycle

PCR involves three general steps: Denaturation, Annealing, and Extension.

Denaturation: Denaturation involves heating the ds-DNA to completely separate it into two molecules of ss-DNA. It occurs at a temperature around 95°C to break the hydrogen bond on the complementary bases (A and T; G and C) of the ds-DNA. These ss-DNA are ready for primer binding.

Annealing: The denatured, single-stranded target DNA is bonded with 15-30 nucleotide-long ss-DNA fragments called primers. Primers bind their 3’ ends to the complementary ss-DNA. This process typically occurs at temperatures ranging from 50°C to 65°C. This process is called annealing. Annealing provides a reference point for synthesizing a new DNA strand by allowing DNA polymerase to initiate amplification while specifically targeting the sequence between the forward and reverse primers.

Extension: Extension (or elongation) involves the enzyme DNA polymerase. The interaction between primers and the target DNA causes the start of synthesis of new ds-DNA during extension. DNA polymerase then works to add a nucleotide (dNTPs) at the 3’ end of the primers, which extends the DNA strand from 5’ to 3’ direction. This process is generally carried out at 72°C.

After extension, a new double-stranded DNA molecule is formed. This cycle is repeated 30-40 times until amplification of multiple copies of the target DNA.

Primer Design Strategies

Primers are among the most essential components of a PCR experiment. Appropriate primers are therefore absolutely critical for efficient and effective amplification. Computational tools, such as the NCBI Primer-BLAST and Primer3, are generally used for designing primers.

The following fundamentals need to be undertaken while designing a primer:

- Complementary to target DNA: Primers need to be complementary to the target DNA. Among the two primers, one primer should complement the plus strand (sense/non-template) of the DNA, i.e., oriented in 5’ → 3’ direction, while the other should complement the minus strand (antisense or template) of the DNA, i.e., oriented in 3’ → 5’ direction.

- Non-self-complementary: The plus strand and the minus strand primers (Forward and Reverse primers) must not be complementary to each other. Similarly, the 3’ end of a primer should not be complementary to other nucleotide sequences in the same primer, which could result in the formation of hairpin-loop structures.

- Size: Too short primers result in non-specific amplification, whereas too long primers can lead to slower hybridization. A primer length should ideally range between 15 and 30 nucleotides.

- G-C content: 40-60% G-C content is generally considered optimal for primers. The melting temperature (Tm), stability, and specificity of a primer heavily rely upon G-C content.

- Melting Temperature (Tm): The ideal melting temperatures (Tm) for primers range between 52 and 58°C, which can be expanded to 45-65°C. The melting temperatures for both forward and reverse primers should not differ by 5°C or more for effective amplification.

- G-C clamp: Primers can split apart at the ends due to low stability in bonding. However, when a 3’ end of a primer contains a G-C pair rather than an A-T pair, the stability as well as the melting-temperature increases, as the triple hydrogen bonds set the primers to prevent them from splitting apart.

- Di-nucleotides / Single bases: While designing primers, patterns in nucleotide sequence such as: Dinucleotides {GCGCGCGCGC or ATATATATAT} or single bases {TTTTTT or GGGGGG}, should be avoided. These patterns can hinder the ability of primers to bind effectively to ss-DNA.

Types of DNA Polymerases

Polymerases commonly used in PCR:

- Taq DNA Polymerase: a highly heat-stable thermophilic DNA polymerase derived from Thermus aquaticus

- Hot-start DNA polymerase: a modified version of Taq DNA polymerase that is inactive until the initial denaturation step, and highly effective in reducing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation.

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase: a modified version of Taq DNA polymerase having 3’→5’ exonuclease activity to remove incorrectly added bases during replication. These are used for applications that require extremely low error rates and high accuracy, such as sequencing and cloning.

Based on taxa, DNA polymerases are divided into two different groups: Prokaryotic polymerases and Eukaryotic Polymerases, which are further subdivided into specific types.

- Prokaryotic Polymerases: Polymerases I, II, III, IV, and V are the types of prokaryotic polymerases.

- Eukaryotic Polymerases: Polymerase α (alpha), β (beta), δ (delta), γ (gamma), λ (lambda), and ε(epsilon) are among the various types of eukaryotic polymerases.

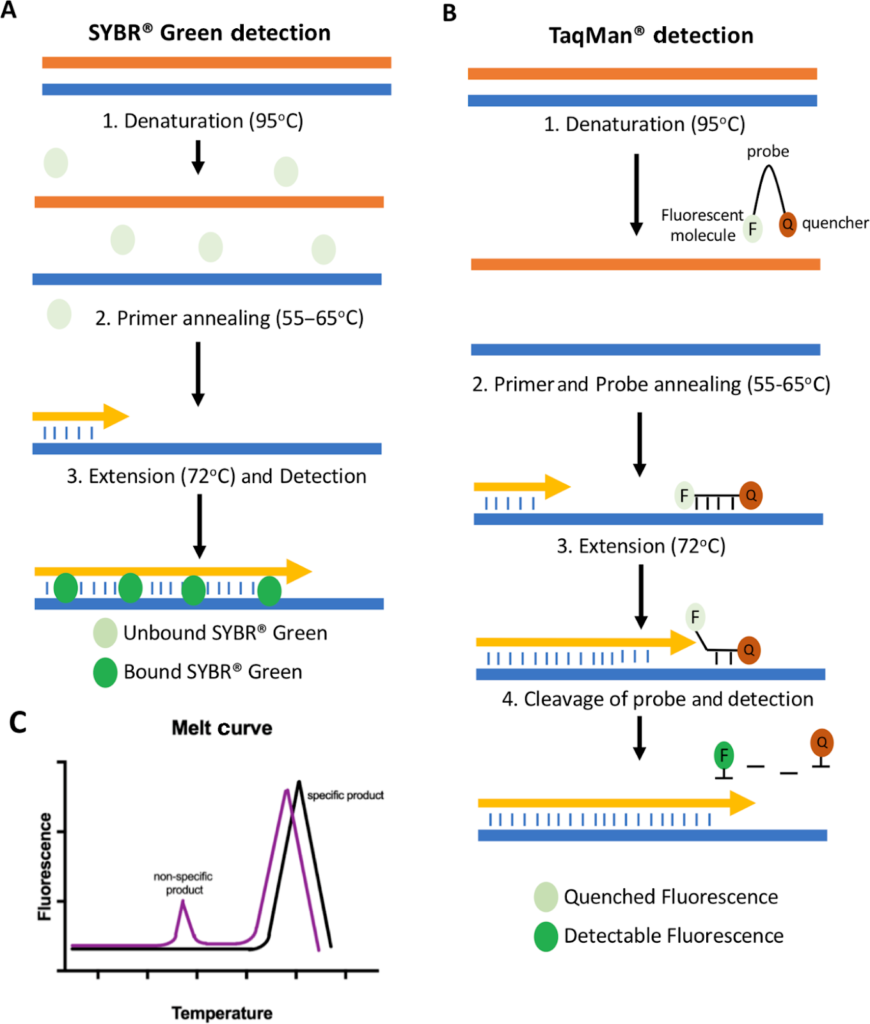

Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

Real-time PCR or quantitative PCR, or quantitative real-time PCR, involves simultaneous amplification and quantification of target DNA. During qPCR, the amount of amplicon formed is constantly monitored throughout the reaction by using fluorescent-based dyes or probes. The fluorescence of dyes or probes is directly proportional to the quantity of amplicon formed. This technique is essential for both qualitative and quantitative determination of target DNA.

Advantageous over PCR:

After conventional PCR, agarose gel electrophoresis is needed to visualize whether amplification has occurred. However, qPCR provides significant advantages over conventional PCR due to its ability to visualize and quantify amplification in real time, without the need for agarose gel.

Detection method in qPCR:

The quantification of an amplicon formed is generally detected using a fluorescent dye or hydrolysis probes.

During DNA elongation, a fluorescent dye, such as SYBR Green, intercalates into the newly formed double-stranded DNA, subsequently emitting a fluorescent signal. Unbound fluorescent dyes do not emit signals.

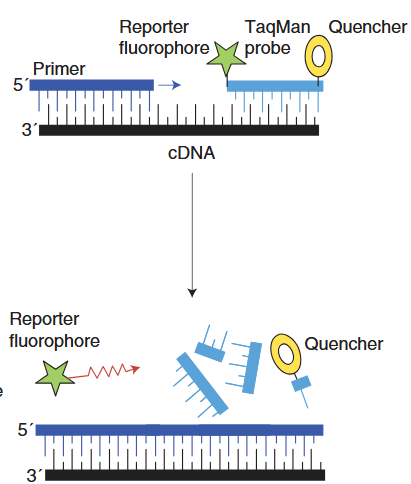

Hydrolysis probes, such as TaqMan Probes, are oligonucleotide probes that hybridize with one of the newly formed DNA strands. A probe has a reporter fluorescent dye at the 5’ end and a quencher dye at the 3’ end. After primer hybridization, during the elongation process, the DNA polymerase cleaves the probe, which separates the reporter and the quencher. This causes the reporter molecule to generate a fluorescence signal, and fluorescence is hence detected by the thermal cycler.

Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

Reverse transcription PCR contains RNA as the starting nucleic acid (in contrast to DNA during conventional PCR) to create complementary DNA (cDNA) by the action of an enzyme, Reverse Transcriptase (RT).

Primers during RT-PCR:

Either oligo(dT) or random hexamers are utilized as primers to create cDNA. Oligo(dT) primers are a sequence of polyT (poly-deoxythymidine) nucleotides which attach to the polyadenylated (polyA) tail of RNA (especially mRNA), whereas random hexamers (6-base long random nucleotide sequences) bind at multiple points along the RNA template. As only mRNA constitutes a polyA tail, whereas tRNA and rRNA do not contain a polyA tail, oligo(dT) and random hexamers are generally used together during cDNA synthesis to create amplification of total RNA (mRNA, tRNA, and rRNA). The generated cDNA is then amplified by DNA polymerase to create multiple copies either by conventional or qPCR.

RT-PCR can occur either in one or two steps, either separating the cDNA synthesis and qPCR amplification or involving both steps in a single reaction.

Source: (Adams, G., 2020), doi: https://doi.org/10.1042/BIO20200034

Source: (Manit et. al., 2005), doi: 10.1586/14737159.5.2.209

Troubleshooting Common Issues in Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

During PCR, failure to amplify or the generation of multiple unamplified products can be common issues. Therefore, stringent troubleshooting is necessary.

- Make sure the thermal cycler is in effective working condition. Confirm that no human error was involved, and that all the reagents were added to the reaction mixture. Use positive and negative controls.

- Even when there’s no amplification in the case of positive control, check the primers and reagents with known, previously used primers.

- If there’s still no amplification, the reagent is bad. Re-perform amplification with new reagents.

- If only the positive control is amplified, the template DNA could be wrong. Double-check the template quality and quantity. A very low-quality, diluted, or contaminated template can lead to no product formation.

- If positive control & samples amplify, the primers are wrong. Adjusting the annealing temperature (Tm) or redesigning primers is necessary.

- Non-specific products (smears or multiple bands) can form when PCR specificity is low. It occurs when primers anneal to sequences rather than targeted sequences. Use fresh lyophilized primers previously tested to work well. If the problem continues, adjust the annealing temperature or redesign the primers as necessary.

- Determine if any reagents are contaminated with inhibitors or are inactive. Prepare new reagents (stocks and working solutions) and systematically add one reagent at a time, changing the reaction mixture each time before running a PCR.

- If the primer concentration is high compared to the template, they self-anneal and form primer dimers. Alter the concentration according to the template.

Applications of PCR in Diagnostics and Research

Diagnostics:

- Reducing pathogens culture and direct detection of pathogens such as Hepatitis B Virus, SARS-CoV-2, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB), etc., as well as characterization of their subtypes, genotypes, variation, mutation, and genotypic resistance.

- Prenatal and neonatal screening for genetic disorders such as: Trisomies (21,18, and13) and aneuploidies in sex chromosomes.

- Applicable in oncology to detect and characterize cancer cells that are otherwise undetectable.

- Forensics to identify individuals for criminal or hereditary analysis from minute samples.

Research:

- Commonly applied in research laboratories for the identification of microorganisms in various environmental and clinical samples.

- PCR-based techniques, such as metagenomics, allow for the profiling of microbial communities based on their specific genetic markers.

- qPCR and RT-qPCR are applied in gene expression studies by quantification of mRNA levels to study intracellular responses to the environment, treatment, or diseases.

- Reconstruction of genomes of extinct species, study of evolutionary history, and exploration of genetic relationships can be performed from fossils and ancient remains.

Conclusion

PCR is one of the most significant discoveries in molecular biology, which enables precise amplification of DNA from minute quantities by integrating fundamental principles of enzymology and nucleic acid hybridization. The applications of PCR extend to the field of research, diagnostics, and biotechnology. It remains a foundational and effective tool in basics as well as advanced studies in biological sciences.

References

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1993/mullis/facts

Khehra N, Padda IS, Zubair M. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) [Updated 2025 Jul 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589663/

Lorenz T. C. (2012). Polymerase chain reaction: basic protocol plus troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE, (63), e3998. https://doi.org/10.3791/3998

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/probe/docs/techpcr

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast

Shen, Z., Qu, W., Wang, W. et al. MPprimer: a program for reliable multiplex PCR primer design. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 143 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-11-143

https://www.thermofisher.com/blog/behindthebench/pcr-primer-design-tips

https://www.addgene.org/protocols/primer-design

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/dna-polymerase

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16460794

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-418687-3.00023-9

Grace Adams; A beginner’s guide to RT-PCR, qPCR and RT-qPCR. Biochem (Lond) 22 June 2020; 42 (3): 48–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1042/BIO20200034

Arya, M., Shergill, I. S., Williamson, M., Gommersall, L., Arya, N., & Patel, H. R. (2005). Basic principles of real-time quantitative PCR. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics, 5(2), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737159.5.2.209

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bdq.2015.11.001

https://www.scielo.br/j/bjm/a/xGvDxSJK68CmJqwzkTLncZv/?format=html&lang=en

https://www.veritasint.com/blog/en/qf-pcr-what-is-it-and-what-is-it-used-for-in-prenatal-diagnosis

Burchill, S. A., Bradbury, M. F., Pittman, K., Southgate, J., Smith, B., & Selby, P. (1995). Detection of epithelial cancer cells in peripheral blood by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. British journal of cancer, 71(2), 278–281. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1995.56

https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1365-2958.2005.04805.x

https://www.qiagen.com/us/knowledge-and-support/knowledge-hub/bench-guide/pcr/introduction/enzymes-used-in-pcr